This story is developing.

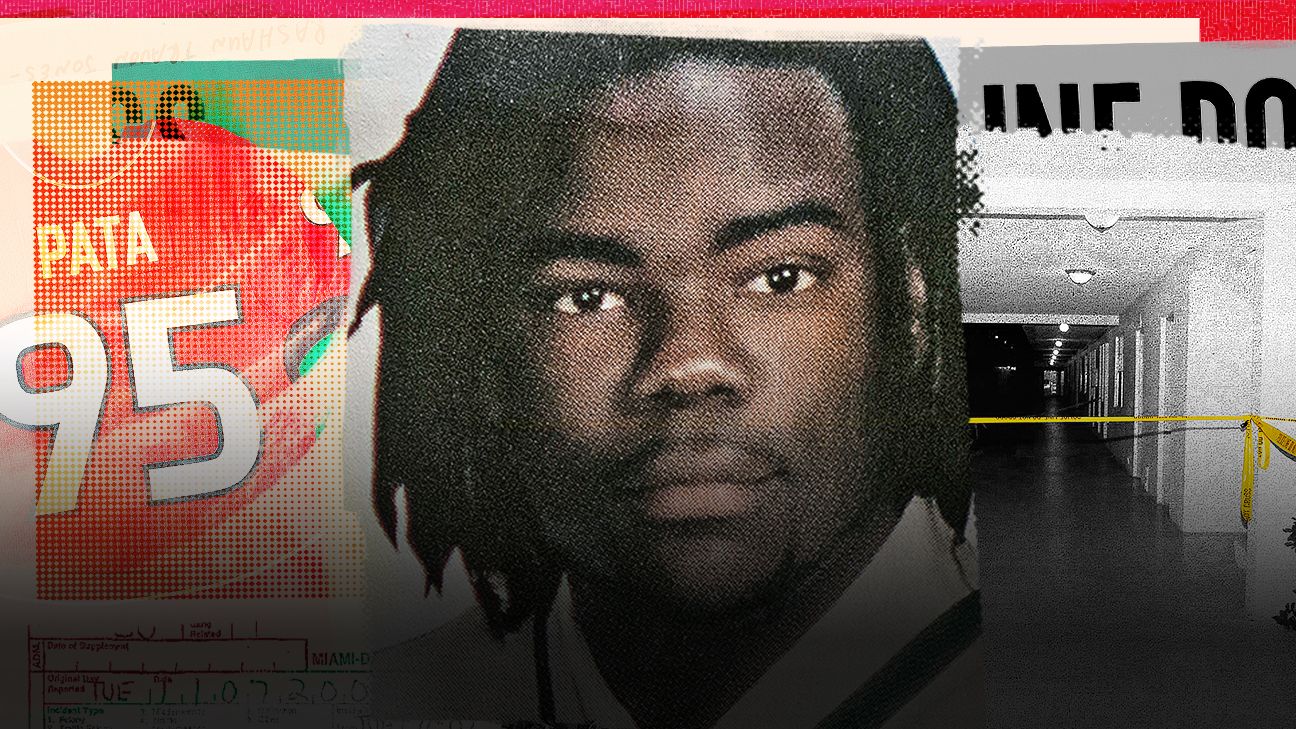

Police arrested a former Miami football player Thursday in the November 2006 shooting death of teammate Bryan Pata, nearly 15 years after the crime and nine months after an ESPN investigation pointed out missteps in the long-stalled police inquiry.

Miami-Dade Police said U.S. marshals arrested Rashaun Jones, 35, on a first-degree murder charge in the killing. In a video issued on Twitter, Det. Juan Segovia thanked the Pata family and the community for keeping the pressure on to solve the case.

“The community never stopped contacting us,” Segovia said. “Even if we got a thousand tips and only one was the one that actually put the pieces together, that’s what it took, and that’s exactly what happened in this case.”

“I can only hope that this brings the Pata family a little bit of closure and a little bit of satisfaction.”

The Miami Herald reported that Jones was arrested in Marion County, in central Florida. Segovia said Jones was awaiting extradition to Miami. Further details on what led police to make the arrest were not immediately available.

In a brief April 2019 telephone conversation while ESPN was investigating the case, Jones said he knew police and even some former teammates suspected him of killing Pata, but he denied any involvement.

“What happened 12 years ago, happened 12 years ago,” he said at the time. “It’s got nothing to do with me. … I didn’t do it.”

Last year, Jones’ wife Ishenda Jones wrote in a text to ESPN that, “[Rashaun’s] comment was he was innocent. He did NOT kill Bryan. Miami-Dade found no evidence against my husband.”

The arrest came one week after what would’ve been Pata’s 37th birthday. On Nov. 7, 2006, someone shot Pata in the head as he got out of his SUV in front of his apartment complex four miles from the Miami campus. It was around 7 p.m. and Pata had just returned from afternoon practice; he was months away from being selected in the NFL Draft.

Jones was long considered a suspect in the 15-year-old homicide, a fact revealed last November in the ESPN report that traced the police investigation and outlined various theories – as well as doubts from Pata’s family that police had the commitment and skill to solve the case.

Police said publicly for years that they had no one suspect, but during court proceedings last summer in a battle with ESPN over public records, an officer supervising the investigation said police “have a strong belief who killed Bryan Pata,” and had come close to arresting this person at least a decade earlier.

Jones and Pata had a history of arguments and fights, and Jones had previously dated Pata’s girlfriend, Jada Brody, according to interviews and documents ESPN obtained. Brody cooperated with police around the time of the shooting, but she expressed irritation when police returned to ask questions months later, according to police records. The records do not note her saying anything about Jones’ possible involvement. Prior to publishing its 2020 story, ESPN reached out to Brody for more than two years by phone, text message, social media and through friends and relatives. She never agreed to an interview.

In interviews with ESPN, police theorized that the shooter had been waiting for Pata, possibly in the bushes or behind a dumpster. Police have never found anyone who saw the shooting, and no security cameras in the area captured it. Some people interviewed at the apartment complex reported hearing loud voices, while others heard gunshots, according to police.

In a 2019 interview, Lt. Rudy Gonzalez told ESPN that police interviewed a resident who said he was walking in the parking lot the night of the killing when he saw a man running from the scene. The resident gave them enough of a description to generate a sketch, and records indicate a lineup was shown to an unidentified person. But police have declined to release the sketch or say if it matched any possible suspects.

In March 2020, ESPN sued Miami-Dade for withholding and redacting records in the case, which the network argued should be public because the case was no longer active. But police disagreed it was dormant, and they promised a renewed effort.

Lt. Joseph Zanconato, who was later transferred out of the homicide unit, told the judge that police were just “a puzzle piece” away from closing the case. When asked whether the department would make an arrest “in the foreseeable future,” Zanconato answered: “Yes.”

Police had interviewed dozens of people and generated more than 4,000 pages in the case file with references to nightclub fights, stolen rims, jealous girlfriends, federal agents and even an alleged jailhouse confession. But notes and material pertaining to Jones featured prominently.

Police had interviewed and/or run background checks on more than 100 people. Each of their files had a cover sheet before the information. The cover of Jones’ file in the case report is the only one to note the subject as “suspect.” And sentences blacked out in the middle of a page that had other details about Jones were said to be dealing with “our primary person of interest,” according to court testimony.

In an interview with ESPN, one former teammate recalled a fight between Jones and Pata. According to that account, Jones issued a warning as the two were separated: “Boy, you might as well go ahead and clip up.”

On the night of the killing, documents and interviews indicate Jones was notably absent from a mandatory team meeting called by coaches. He’d been suspended that day after testing positive for marijuana, his third failed drug test.

Jones would later tell police that he was home alone the night Pata was killed, and that when he heard of Pata’s death, he headed to the Hecht Center, presumably for the meeting. But other witnesses told police, and more than a dozen ex-players told ESPN, that they had no recollection of Jones being there. Police noted in their report that Jones had given a false alibi.

ESPN reviewed police notes that indicate Jones called a fellow Miami athlete to borrow money that night to go out of town. Police subsequently interviewed the athlete, who spoke to ESPN on the condition that he not be named but confirmed that Jones did ask for money; he declined to comment further. Coral Gables Police Chief Ed Hudak, a law enforcement liaison for the Hurricanes at the time, said that as he spoke with players at the football facilities on the night of Nov. 7, Jones’ name kept coming up.

“There was a very strong sentiment [Jones] had something to do with it,” Hudak said. “When that was brought up to me by the players, I made sure that the detectives had that. What came of those leads, I don’t know.”

In 2017, police and Pata’s relatives had a press conference to ask publicly for leads and tips. Then, and in the next three years as ESPN journalists worked on the story, officers repeatedly said that they believed there was someone out there – apart from the shooter – with first-hand information, and they needed that person to come forward. In September 2020, Miami-Dade Police largely prevailed in the records lawsuit filed by ESPN, in part because officers vowed they had renewed their case and were likely to make an arrest in the “foreseeable future.” Around that time, the officers who had been working on the Pata investigation either retired or were removed from the case. Police Maj. Jorge Aguiar, who took over the Miami-Dade homicide bureau in fall 2020, told ESPN last fall that he had assigned Det. Juan Segovia, one of the original detectives on the Pata case, to take over. He said Segovia has been reinterviewing prior witnesses, but he gave no further details. After the ESPN story published, Aguiar stopped responding to emails and voicemails seeking updates.

Jones has been charged and convicted of a variety of criminal traffic and drug-related offenses over the years, including an arrest and same-day release in May in connection with a second-offense driving with a suspended license citation in Columbia County.

Jones is listed on the private-coaching website CoachUp, which says that he has 10 years of experience training adults, kids and teenagers. The site says he volunteered with the football team at his alma mater, Columbia High School. At the top of his page is a quote: “(I’ve) seen what mistakes not to make when you have the whole world in your hands!”