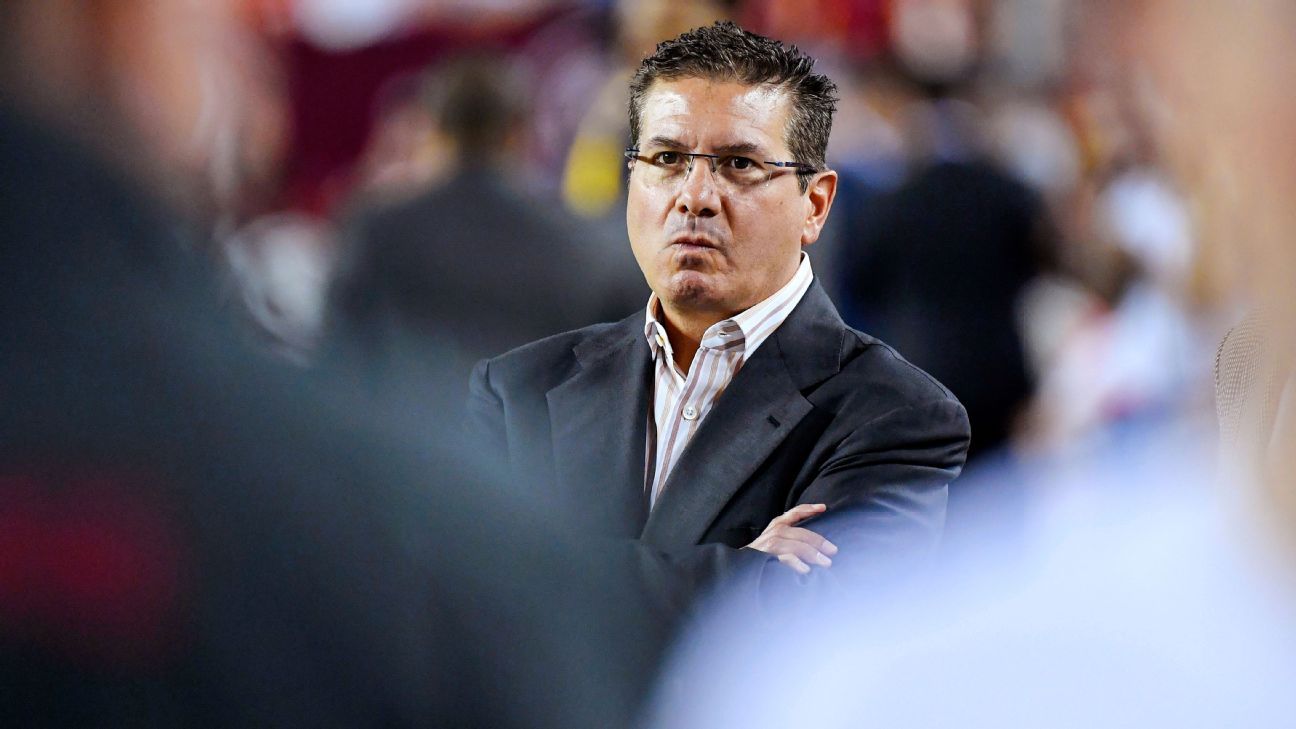

Washington Commanders owner Daniel Snyder “permitted and participated” in the team’s longtime toxic work culture and obstructed a 14-month congressional inquiry by dodging a subpoena, working to dissuade and intimidate witnesses from cooperating, and claiming more than 100 times in testimony that he could not recall answers to basic questions, according to the final report of the U.S. House of Representatives Committee on Oversight and Reform.

The committee’s 79-page report released Thursday also comes down hard on the NFL, concluding that the league was complicit in Snyder’s efforts by not cooperating with the congressional inquiry and by burying a 2020-21 investigation of the Commanders’ workplace led by attorney Beth Wilkinson, the results of which have never been fully released.

“We saw efforts that we have never seen before, at least I haven’t,” said Rep. Carolyn Maloney, D-New York, who chaired the committee. “The NFL knew about it, and they took no responsibility.”

NFL officials “were acting like they were doing something,” Maloney told ESPN. “Then they turn around and fix it so she can’t talk. Her report is never going to be made public, yet she was supposed to be hired to address it. The hypocrisy. The coordinated effort to hide what they acknowledged.”

The congressional report, citing allegations of harassment and abuse against several other teams, says the NFL has put the interests of league owners ahead of NFL employees, failing to protect them or ensure that victims can speak up without fear of retaliation.

“The NFL chose to bury Ms. Wilkinson’s findings and whitewash the misconduct it uncovered,” the committee’s report says. “Rather than seek real accountability, the NFL aligned its legal interests with Mr. Snyder’s, failed to curtail his abusive tactics, and buried the investigation’s findings.”

An NFL spokesperson contacted by ESPN Thursday said the league had not seen the report and would not comment.

The Commanders have attacked committee efforts as driven by partisan politics and have said Snyder and the team cooperated fully with investigators. Spokeswoman Jean Medina released a statement attributed to team attorneys John Brownlee and Stuart Nash that said the report “does not advance public knowledge of the Washington Commanders workplace in any way.”

“These Congressional investigators demonstrated, almost immediately, that they were not interested in the truth, and were only interested in chasing headlines by pursuing one side of the story,” the statement said. “Today’s report is the predictable culmination of that one-sided approach. There are no new revelations here.”

Republicans on the committee issued a memo in response to the report, saying that “The Democrats’ sham investigation into the Washington Commanders has been an egregious waste of taxpayer-funded resources” and that Democrats have misused a committee that should be focused on the government.

“No foundation exists for conducting congressional oversight of the Team,” the memo says. “Simply put, Congress cannot provide any additional relief or remedies to any of the aggrieved parties. Why, then, has the Committee investigated a professional football team and targeted an individual team owner? Committee Democrats have chosen to weaponize the power of Congress against a single private workplace.”

The GOP memo also joins in Snyder’s refrain that former team president and general manager Bruce Allen is to blame for the team’s toxic culture; Allen counters that he didn’t work for the team during many of the years in question. The Republicans released 57 emails and documents, including dozens of images of nude and near-nude women that they say came from Allen’s work account.

“These emails show that under Allen’s leadership there was a toxic workplace — one that has since been reformed based on independent third-party reviews of the team’s culture,” the memo says. “Committee Democrats have not identified or presented any similar emails or documents identifying any racist, misogynistic, or homophobic behavior from Dan Snyder.”

In addition to its report, the House committee released excerpted transcripts from sworn testimony Snyder gave remotely from aboard his yacht in July and from September testimony by Allen.

Among key revelations in the committee report and transcripts:

-

During his deposition, Snyder told investigators, “I’ve said numerous times, and continue to state, we apologize for any workplace misconduct of the team.” But the investigators note that Snyder “continued to blame others around him and minimized the experiences of more than 100 current and former employees.”

-

Under oath, Snyder “admitted to using private investigators,” the report says, but Snyder claimed to be “unaware” whom his investigators approached and did not “remember” having conversations with his counsel about the individuals targeted. “Mr. Snyder could recall very little when questioned about allegations of misconduct against him, including specific allegations raised in recent press stories,” investigators note.

-

In his testimony, Allen recounted his encounter with a private investigator Snyder hired to follow him, and he also swore that Snyder once talked with him about hiring a private eye to follow NFL commissioner Roger Goodell.

-

Although the NFL appeared on the surface to have cooperated with committee requests for documents, much of what the league provided was “news articles, press clippings, and public court records.” Investigators said the league “refused to turn over” at least 40,000 documents collected by Wilkinson during the league’s internal investigation, including Wilkinson’s written findings presented to the NFL during her investigation.

-

Despite claims by Snyder’s attorneys that the team released former employees from restrictions placed on them by nondisclosure agreements, “a significant number of potential witnesses” were unable to share their experiences with investigators either out of fear of retaliation or because Snyder and the Commanders would not release them from their “confidentiality obligations.”

-

Allen testified that an NFL executive indicated to him that the Commanders were behind the leak of racist and misogynistic emails linked to former Las Vegas Raiders coach Jon Gruden.

As the committee finishes its work, the NFL continues its second investigation of Snyder, this time led by former Securities and Exchange Commission chairperson Mary Jo White. And the attorney general of Washington, D.C., has sued the team, the NFL and Goodell on allegations of financial improprieties related to season-ticket deposits.

ESPN reported last month that the U.S. attorney’s office in the Eastern District of Virginia also has opened a criminal investigation into the financial allegations. On the same day, Dan and Tanya Snyder announced they had hired Bank of America to explore potential transactions, and a spokesperson said they were exploring all options.

Snyder testified he ‘can’t recall’

The report says Snyder claimed more than 100 times under oath that he could not recall or was unaware of “basic information about his role as the owner of the Commanders.” Issues Snyder claimed not to remember included hirings and firings, his knowledge of alleged sexual harassment by senior team officials and at least seven presentations made by his lawyers to the NFL during attorney Wilkinson’s investigation. He also said he did not recall his attorneys offering money to former employees in exchange for signing nondisclosure agreements during that investigation.

On the topic of team executives tasking employees to make unauthorized videos of naked cheerleaders, Snyder invoked “I can’t recall” seven times in one excerpted passage of testimony. He swore he’d never seen what he called “the purported videos” and had no recollection of what he or the team did about them, the transcript says.

The committee’s report also details the genesis of a $10 million fine the NFL said it levied against the Commanders on July 1, 2021, after the Wilkinson report. According to the report, Snyder’s legal team negotiated the terms of the fine, allowing Snyder to pay $5 million to the NFL, with the other $5 million sent to approximately 22 charitable organizations within the Washington region, a deal that “may have allowed the Team to take tax deductions for its charitable contributions and payments to the League, thereby conferring the Commanders a benefit.”

Committee staff recommended that Congress “should consider prohibiting professional sports team owners from taking tax deductions on fines or penalties paid in connection with workplace misconduct investigations.”

Under NFL rules, Goodell did not have authority to levy the fine unless he received the approval of two-thirds of the team owners at a special league meeting, according to investigators. Snyder attorneys told the committee that, “after some discussion” between the NFL and Snyder’s lawyers, the two sides agreed on the $10 million sum. They also revealed to investigators that Snyder’s representatives “were actively involved” in the league’s announcement of the fine and Wilkinson’s findings.

As part of the committee’s inquiry, Goodell testified before the full committee in June that Snyder “has been held accountable” after facing “unprecedented discipline” that included “being removed and away from the team.”

Since October, there have been mixed signals about whether Snyder has resumed day-to-day operations of the team. ESPN has reported, and Goodell confirmed in an October news conference, that he was operating under the premise that Snyder is still under active investigation and limits imposed on him were continuing.

But in his July deposition, according to the report, Snyder testified that “he had resumed involvement, including by giving ‘advice and help’ when ‘needed’; being ‘updated and kept informed’ by team President Jason Wright; and holding meetings with head Coach Ron Rivera about the football season and ‘future’ of the franchise.”

“These various assertions cast serious doubt on the NFL Commissioner’s claim that Mr. Snyder had been ‘held accountable,’ by being removed from team operations,” the committee report says.

Allen testifies about private investigators

Allen also testified that Snyder has tried to persuade other owners to remove Goodell and that he told Allen during the height of the NFL’s national anthem controversy that he wanted to use private investigators to follow Goodell.

“He said at that time, ‘I’m going to follow, I’m going to have him followed, follow the Commissioner,’ You know, I’m going to find something out about him,'” Allen testified.

ESPN first reported in October that Snyder had bragged to associates that he had collected “dirt” on team owners and Goodell to stave off any attempt to force him to sell the Commanders.

Allen, who testified that Snyder made the comments in his office, said he “didn’t think he was serious, because it’s just, it’s a crazy thought, that I’m going to burn down the building next door.”

Allen began to reconsider, however, once he discovered other former employees had encountered private investigators hired by Snyder’s attorneys. “Now, after I’ve read about everyone who’s getting followed around the country, I don’t know if it was true or not,” Allen testified. “And then, obviously, when it occurred to me, it was like, ‘Wow.'”

Allen said he first discovered private investigators tailing his movements while moving into a new home in Arizona in March 2021. He testified that the home was on a narrow street with little traffic and that his wife had noticed an unfamiliar car with its engine running parked outside their home.

“I had made some coffee,” Allen testified. “And I went out. And the gentleman stepped out of the car and he said, ‘Hi, Mr. Allen.’ I said, ‘Well, that’s interesting. You need a cup of coffee? Are you here to serve me with a subpoena or something?’

“He said, ‘No, we’re just here to follow you,’ and something like ‘document your actions.'”

Allen said the investigator identified himself as a former FBI agent and offered a business card, also pointing out an associate in a second car down the street who was waiting in case Allen drove out of the neighborhood another way. Allen said he asked who sent the investigators.

“He said the Washington Football Team, which they weren’t the Commanders yet,” Allen said.

Allen said that the man followed him to the rental house he was moving from to get some more boxes and that another investigator was waiting there.

“I thought it was despicable,” Allen testified. “And it’s worse for others. I don’t know if they followed my wife. … But when I’ve read some of these other testimonies, I felt for people who went through similar situations.”

He said the surveillance included the use of drones “outside the back of our house” and added that an investigator confronted a construction worker at the home, saying, “Tell us about Bruce Allen.”

The committee also released video of a private investigator captured on a home surveillance system in April 2021 as he attempted to gather information on former cheerleader Abigail Dymond Welch, one of the women investigators believe was captured in videos created from the outtakes of swimsuit calendar shoots.

Maloney characterized Snyder’s alleged use of private investigators “extreme behavior” that she had never encountered in three decades on Capitol Hill. “He was intimidating the workforce and the executives. Anyone who spoke out, he had private investigators go to their home and track them. Going to a cheerleader’s home with their children and try to offer hush money and try to intimidate them not to talk anymore.”

The committee had previously revealed, in a 29-page memorandum released in June, that the law firm Reed Smith sought to “harass and intimidate” and “secure the silence” of former employees and possible witnesses during the Wilkinson investigation.

Reed Smith partner Jordan Siev told ESPN in October that it “had no knowledge of any efforts to investigate or compile information” on NFL owners, executives or Goodell. Siev did not respond to questions about whether Reed Smith commissioned investigations on former Commanders employees.

In the newly released transcript, committee investigators ask Snyder specifically about the firm, asking, “Did Reed Smith send private investigators to the home of Bruce Allen?”

Snyder replied: “I’m not sure. I’m unaware.”

In his deposition, Snyder told committee staff that the private investigators were employed to gather information for a defamation lawsuit in India, and were not part of any effort to intimidate or retaliate against those employees who came forward.

ESPN’s October report cited multiple legal and team sources as saying Snyder used the Wilkinson investigation as a “tip sheet” for his law firms to form an “enemies list.” The committee report states that ESPN’s reporting was “consistent with evidence uncovered by the Committee.”

Snyder has denied launching what the committee has called a “shadow investigation.” He testified that a 100-page dossier of information on his former employees, including cheerleaders and Allen, “had nothing to do” with the Wilkinson investigation, even though his legal team presented the contents of the dossier to the NFL and to Wilkinson.

The committee report spends several pages fleshing out a timeline that punches holes in Snyder’s defense of the dossier. “Mr. Snyder suggested that the private investigators employed by his lawyers may have ‘made a mistake and went somewhere wrong,'” the report says. “However, he insisted that they ‘only used investigators regarding the India lawsuits.'”

Attempts to blame Allen for toxic culture

In his deposition, Allen testified that he informed Lisa Friel, the NFL’s senior vice president and special counsel for investigations who was helping to oversee the Wilkinson investigation, about his experience with the private investigators in April 2021.

He said Friel gave him the impression that she was “not shocked” by his story and called Snyder’s actions “conduct detrimental” to the integrity of the league.

“They knew,” Maloney said. “They knew. They called it detrimental conduct that they then become complicit in by hiding the detrimental conduct. So it could continue, literally could continue. And that was, to me, irresponsible beyond belief.”

Friel also informed Allen of Snyder’s efforts to blame him for the team’s “decades-long toxic culture,” telling him of the team’s presentations to the NFL about Allen’s role in day-to-day operations of the franchise, according to his testimony.

Friel also “indicated that the Commanders were responsible for the leak” of racist and misogynistic emails linked to Gruden that appeared in the New York Times and the Wall Street Journal in October 2021, Allen testified. Congressional investigators had previously uncovered evidence that Snyder’s lawyers had provided those emails to the league in the summer of 2021 as part of Snyder’s effort to deflect blame onto Allen.

Allen testified that when he learned about the leak to the Wall Street Journal, he called Friel, who told him, “We didn’t do it at the league office. It came out of their side.”

The report noted that the day before Allen was scheduled to be deposed, Snyder’s legal team sent the committee unsolicited emails that “contained embarrassing language and inappropriate content” that had been sourced from Allen’s team account, including emails that had already been leaked to the press. The report noted that Snyder’s legal team had leaked other emails, documents and photographs in an attempt to discredit several other congressional witnesses who made allegations against the team.

“The committee’s investigation found that the NFL was aware of Mr. Snyder’s surveillance, harassment, and intimidation of his accusers throughout the Wilkinson investigation,” according to the committee report.

In his testimony, Allen told investigators that he interpreted the email “leak” as an attempt by Snyder “to send a message” to Allen that he “be careful,” and that Snyder “owns me with these emails, which affect my co-workers, the alumni, my family and friends.”

Ultimately, the report concludes, “Many of the emails that Mr. Snyder leaked were unrelated to the Committee’s investigation or were presented in a misleading way so as to imply wrongdoing.”

Committee says league efforts aided Snyder

The report says investigators were hamstrung by the league and the team refusing to release as many as 40,000 documents related to the Wilkinson investigation.

In February, the committee released the contents of a previously secret “common-interest agreement” between the league and the team that it had obtained. At least one source close to the investigation calls the agreement “very unusual” and not a something often done within the league. As ESPN reported in February, the agreement essentially gave Snyder veto power over the release of any documents or information related to the Wilkinson investigation.

At the time, NFL spokesman Brian McCarthy told ESPN that “the League, and not the team, has and will determine which information it is in a position to produce.”

But the committee’s final report gives multiple examples of how Snyder and the team “exerted privilege with the NFL’s release of information” by preventing the release of not only Wilkinson’s findings, but many other documents, including several PowerPoint presentations made by the team to the NFL and Wilkinson, videos containing the outtakes of the cheerleader calendar shoots and a 2018 human resources audit showing deficiencies in the team’s HR department.

The committee also was unable to obtain a confidential settlement relating to Snyder’s alleged sexual assault of the woman on his plane in April 2009, now the subject of Mary Jo White’s investigation.

“The NFL became cooperative in hiding what was happening by entering a legal common-interest agreement that really silenced all the of the work trying to address it,” Maloney said.

The committee report details how Snyder’s attorneys tried to prevent Wilkinson from interviewing the former female employee who accused Snyder. The report states Snyder and the team would not release her from the agreement she signed, preventing Wilkinson from interviewing her.

The report cites ESPN’s report in October that detailed how the woman’s attorney had “flatly rejected” an offer from Reed Smith attorneys of a “seven figure” sum if she agreed “not to speak to anyone about her allegations against Snyder and her settlement with the team.” Snyder’s attorneys have denied offering additional money to his accuser in exchange for her silence.

Lawyers for the NFL told the committee investigators that while the league was aware of a “dispute” that team had with an employee, the team did not disclose “the specific nature of this allegation” for more than 10 years, and only after the Washington Post began detailing issues of sexual harassment within the franchise in 2020. But the report notes that the Wilkinson investigation found no violation of league policies for failing to report a sexual assault allegation.

In its conclusion, the committee asserts that the NFL is not interested in protecting its employees from workplace harassment, highlighting three other scandals in recent years: allegations of sexual and racial harassment by former Carolina Panthers owner Jerry Richardson; complaints that Las Vegas Raiders owner Mark Davis ignored allegations of a hostile work environment; and revelations, first revealed in an ESPN report, that Dallas Cowboys owner Jerry Jones paid $2.4 million to resolve allegations that longtime senior executive Richard Dalrymple secretly recorded Cowboys cheerleaders while they were undressing and taking “upskirt” images of Charlotte Jones Anderson, Jones’ daughter. Dalrymple, who denied the allegations, retired after a 32-year career with the team days before the report.

The NFL “has failed to take key steps to protect employees or prevent workplace misconduct from occurring across the league,” the report says.

According to an internal document obtained by the committee, the NFL’s reporting requirements do not consider “workplace complaints of sexual harassment” including “non-physical sexual harassment, discrimination, retaliation” to be “conduct that undermines or puts at risk the integrity of the NFL, NFL clubs or NFL personnel” under the NFL’s Personal Conduct Policy.

Rather, the committee concluded, “The NFL’s ongoing failure to take workplace misconduct seriously is compounded by its own policies that are designed to protect the interest of club owners.”

Attorneys Lisa Banks and Debra Katz, who represented more than 40 former Commanders employees, said the report “definitely details not only the extensive sexual harassment that occurred, but also Dan Snyder’s involvement.”

“Because neither the team nor the NFL was willing to reveal the extent of what occurred or hold accountable those responsible, and instead tried to obstruct any efforts to do so, Congress was compelled to take action,” the attorneys said.

What’s next?

Committee staffers recommended that Congress should require the NFL and its clubs “demonstrate compliance with state and federal employment laws as a condition to continue to benefit from federal antitrust exemptions as well as tax-exempt bonds used to finance construction and renovation of sports stadiums.”

Several congressional measures have come out of the Commanders investigation. Democratic committee member Jackie Speier of California co-sponsored legislation in February entitled “No Tax Subsidies for Stadiums Act” that would eliminate tax breaks used by professional sports teams. Chairwoman Maloney introduced a bill to require employers to give prior notice and receive consent to take and distribute professional images of employees, and to prohibit the use of nondisclosure and confidentiality agreements to prevent or interfere with an employee’s ability to disclose harassment, discrimination or retaliation in the workplace.

The future of that legislation is uncertain. Speier is retiring and Maloney lost her primary race in August, while Democrats lost the House majority in November. Republican James Comer of Kentucky has already indicated that the Republican party has no interest in pursuing the investigation any further when he becomes the new chair of the oversight committee in January.

“This has become a tremendously important issue to America,” Maloney says. “The NFL is one of our most respected corporations. It employs a lot of people. Many people look up to them as role models and they should be setting a standard of treating their women and men with respect.”