There’s a very solid chance — about 50-50, depending on where you get your projections — that this European soccer season ends with both Napoli‘s first Serie A title since 1990 and Arsenal‘s first Premier League title since 2004. Neither of these clubs is a Leicester City, but considering what we’ve grown accustomed to in this sport, with entrenched power and rich-get-richer tendencies, those two results would represent quite the tectonic shift.

Consider some of the other things that remain on the table (with far greater than 0% odds) as we enter the season’s home stretch:

– Liverpool‘s worst league season since 2012

– Chelsea‘s worst season since 1991

– An end to Bayern Munich‘s 10-year Bundesliga title reign

– Brighton and Union Berlin making the Champions League for the first time

– Real Sociedad and/or Real Betis making it for the first time since 2014 and 2006, respectively

– Napoli winning the Champions League

We knew this could be a pretty odd season, what with the whole “worse-than-normal fixture congestion in the fall, followed by a long World Cup break” thing. And while order could still restore itself in the coming weeks — Bayern runs away with the Bundesliga, Liverpool charges back into the Premier League top four while Manchester City wins the league, a more well-established (read: richer) power wins the Champions League — there’s no denying that, on average, Europe’s best and richest teams aren’t dominating quite as much as they usually do this season.

– Stream on ESPN+: LaLiga, Bundesliga, more (U.S.)

Was that all because of oddity and the winter World Cup? Or is there something else going on?

How much worse are the best teams?

To attempt an answer here, we’re going to look at a specific batch of clubs: the current top 10 in the UEFA coefficients, aka the 10 teams that have been most consistently awesome in European competitions over the past five years. They are Bayern Munich, Manchester City, Liverpool, Chelsea, Real Madrid, Paris Saint-Germain, Manchester United, Barcelona, Juventus and Ajax.

That’s a pretty good list of heavyweights right there, and in terms of league points, six of them — including each of the top four — are on pace for worse finishes in 2022-23 than in 2021-22.

Here are the 10 teams, listed with last year’s league point total, this year’s current pace (based purely on current points per game) and the change they’ve seen in their rating at EloFootball.com. (Elo ratings basically amount to a point exchange — beat an opponent, and you take some degree of Elo points from them — so they can be extremely useful for this type of exercise. Beat a bad opponent, and you trade a few points; beat a good opponent, and you trade more.)

*We’re going to ignore Juventus’ current 15-point deduction here, since it has nothing to do with on-field performance.

On average, these 10 teams have lost about 9.5 Elo points per team and are on pace for a league finish about 2.1 points lower.

Manchester United have improved nicely under new management, and while Barcelona’s lever pulling could not prevent a memorably dreadful European performance — they failed to qualify for the Champions League knockout rounds for the second straight year, then stumbled immediately in the Europa League (albeit against Manchester United) — it still produced a nice rebound in club form. But their respective rises have not offset the fact that Liverpool and Chelsea have collapsed and reliable league heavyweights Manchester City, Bayern, Ajax and, at least slightly, Real Madrid have all taken backwards steps in league play.

– O’Hanlon: Rating the Premier League’s title, top four, relegation races (E+)

It’s not just the Chelsea and Liverpool collapses dragging everything down either: Teams Nos. 11-20 on the coefficients list (Borussia Dortmund, Inter Milan, Roma, Atletico Madrid, RB Leipzig, Villarreal, Porto, Tottenham Hotspur, Sevilla and Benfica) are also on a pace that’s 2.1 points per team lower in league play, and they’ve dropped an average of 5.8 Elo points despite impressive rises from teams like Benfica and Borussia Dortmund.

Defensive intensity and field-tilting ability: down

Okay, so the best teams are a little worse than normal. In what ways are they worse?

They are pressing less effectively and creating fewer easy scoring opportunities

On average, the 10 teams above have seen their average possession rate fall from 61.4% to 59.9%. They are allowing opponents 4.3 passes per possession (up 5% from last season), and they are averaging 11.1 passes per defensive action, a common measure for defensive intensity. That’s a 4% increase.

Giving opponents a bit less obstruction has created a domino effect of sorts. Opponents are now creating 5% more touches in the attacking third (126.9 per 90 minutes) and 6% more in the defensive box (18.3), and they’re attempting 6% more shots per possession (0.11).

If your foe is finishing more possessions deep on your side of the pitch, then you’re starting more possessions there, too. That means more opportunities to suffer a costly turnover — opponents are starting 2% more possessions outside of their defensive third — and it means you’ve got a longer way to go to advance the ball into dangerous areas. These 10 clubs are now finishing 3% fewer possessions in the attacking third (down to 46.8%), and they are producing 6% fewer touches of their own in the attacking third (209.6) and 4% fewer touches in the box (32.9). This is likely also part of the reason why these teams are producing fewer high-quality shots, too: their average xG per shot is down 8% to 0.12.

Are these humongous changes? Obviously not. These teams are still very good for the most part. But the changes add up, and they result in a few more matches being left to chance.

They are not charging back from behind as well

Arsenal and Napoli are evidently stealing all the comebacks. They are averaging 1.9 and 2.0 points per game, respectively, in matches they trail. When behind, Arsenal’s goal differential per 90 possessions is +2.0 and Napoli’s is a whopping +3.4. The top 10 teams, per the coefficients, averaged a goal differential of +1.4 in these situations last season; this season, that average has been cut in half to +0.7.

There are still some comeback kids in the mix: Ajax are at +2.3 per 90 possessions, Real Madrid are at +2.0 and Manchester City and Bayern are at +1.5. But despite overall improvement, Manchester United (-1.5) have not regained their “Fergie Time” edge just yet — suffering a 7-0 loss to a big rival certainly doesn’t help your averages in this regard — and Chelsea (-0.4) have not been able to claw back into games either. Four of the 10 teams have a negative goal differential when trailing; only one did last year (United again).

Maybe the biggest difference between last season and this season? These teams are occasionally getting thumped. Their xG differential in losses was +0.8 per match last season, meaning they were generating better chances and perhaps getting a bit unlucky. This season, their xGD is -0.3 in losses. Seven of 10 teams are in the negative this year, and none were last year. When they’re losing, they’re actually losing.

What have the “trend-buckers” done to buck the trend?

One common trait the 10 teams above share this season: They’ve all gotten older. Using the average ages found at FBref.com, which are weighted by minutes played, we see that nine of those 10 teams have a higher average age this season than last. Manchester City’s average rose from 27.0 to 27.8, and City, Liverpool (28.2), Chelsea (27.5) and Manchester United (27.6) are all well above the average age of the past five Premier League champions (26.6).

Real Madrid (28.0) and Barcelona (26.5) have both seen their averages rise, too, though that’s not necessarily a bad thing for Barca. Ajax’s average rose slightly after a number of high-value transfers out, Bayern’s is up from 26.8 to 27.2 and Juve’s is up from 27.4 to 28.4. That last one is the largest rise on the list, and it fits: Manager Massimiliano Allegri has a long history of struggling to trust younger players, and currently, only two of their top 12 players from a minutes perspective are under 25.

2:28

Is the LaLiga title race over after Real Madrid’s draw to Real Betis?

Craig Burley and Steve Nicol react to Real Madrid’s 0-0 draw to Real Betis in LaLiga play.

The only team whose age has gone down? PSG, whose average has dropped ever so slightly from 27.8 to 27.6. They officially handed the goalkeeper reins to 24-year old Gianluigi Donnarumma this season and have actually played a couple of the youngsters they added last season, mainly midfielder Vitinha (22) and full-back Nuno Mendes (20).

This creates an interesting contrast with this season’s shining lights. Arsenal’s weighted average age this season is 25.0 and while that’s up from last season’s 24.4, it’s still well below that of anyone above. Napoli’s, meanwhile, fell from 27.9 last season to 27.1, lower than that of eight of 10 teams above.

Is this a massive trend? It’s hard to say, though this is a nice reminder that you don’t have to load up entirely on veterans to have a good squad. Of the top clubs above, the teams whose Elo ratings have fallen are at 27.7 years old on average, and the teams that have risen are at 27.2. Meanwhile, the other biggest risers among Europe’s elite (or nearly elite) are indeed even younger than that.

Here are the 10 European teams that are (A) currently in the EloFootball top 50, (B) not in the top 20 in UEFA’s coefficients and (C) have seen their Elo ratings rise the most in 2022-23: Napoli, Arsenal, Brighton, Newcastle, Lens, Wolfsburg, Brentford, Union Berlin, Marseille and Freiburg. Despite the presence of a couple of particularly old teams — Newcastle at 28.1, Union at 28.5 — these teams’ weighted age averages are 27.1. And whether there’s something to the age thing or not, it’s certainly interesting that their statistics have improved in a way that almost perfectly mirrors how the powers above have regressed:

-

Opponents’ average passes per possession has fallen by 6% (to 4.5), and their PPDA has improved by 9% (to 11.9).

-

They have increased their percentage of possessions starting outside the defensive third by 4% (49.3%), and they are ending 7% more possessions in the attacking third (41.6%).

-

They are creating 13% more touches in the attacking third (171.5), 16% more in the box (26.7), while opponents are down 10% (133.1) and 2% (20.8) in those categories. In all, these 10 risers have gone from commanding 50.8% of all touches in the attacking third to 56.1%, a massive improvement.

-

Tilting the field in their favor has had a predictable impact on the number of shots they’re allowing opponents (down 5% to 0.12 per possession), but it hasn’t made these teams more susceptible to counter-attacks: Opponents’ average xG per shot has dropped 8% (0.10), and in what I define as transition possessions — possessions that start outside of the attacking third and last 20 or fewer seconds — these teams’ average goal differential has improved from +0.0 per match to +0.2.

-

They’re navigating game states better, too. Their average goal differential when tied has risen from 0.3 per 90 possessions to 0.7, but their goal differentials when ahead (from +0.4 to +1.0) and behind (from -0.1 to +0.5) have risen by even larger amounts. Yes, Napoli and Arsenal have been comeback kids, but so have Lens (+2.1), Newcastle (+0.7) and Marseille (+0.7).

Is this a sign that teams are better at solving the rich-club possession game than they used to be, that more teams are “Morocco‘ing” their way up the ladder? It would be fun to think so.

Is it simply a sign that fixture demands and injuries and everything we thought might affect the club game this year are indeed doing so? That’s not nearly as fun, but possibly. Either way, we have to wait to see how the rich clubs respond next year to know the answer.

1:29

Nicol explains how Liverpool thrashed Manchester United

Steve Nicol pinpoints how Liverpool were able to embarrass Man United in their 7-0 thumping at Anfield.

If there’s one statistical development I find particularly interesting here, however, it’s the fact that some of the names on the Most Improved List above are also some of the teams doing the best jobs of both creating numbers advantages and attacking with one-on-ones.

-

The teams on the Most Improved list have increased both their average carries (to 392.5 per match) and progressive carries* (to 67.9) by 9%. Five of the 10 teams — Arsenal, Brighton, Lens, Marseille and Napoli — are over 435 per carries per match, and there are only three teams over 100 progressive carries per match in Europe’s Big Five this year: Manchester City, PSG … and Lens.

-

The improved teams are also attempting 13% more take-ons* (17.7) and 4% more ground duels (70.1), and they are completing 12% more progressive passes (52.0), too.

* StatsPerform defines “progressive carries” as “carries that occur in the opposition half, are greater than five meters and move the ball at least five meters towards the opposition goal,” while “take-ons” are literally “when a ball carrier attempts to beat a defender on the dribble.”

Sky Sports’ Adam Bate recently wrote about Arsenal’s increasingly impressive ability to create one-on-one situations for attackers Bukayo Saka and Gabriel Martinelli, and it certainly bears mentioning that while Saka has the most one-on-one opportunities in the Premier League, Napoli’s transcendent Khvicha Kvaratskhelia has the most in Serie A, too.

The world has gotten used to the best and richest teams in the world playing keep-away and passing nearly literal circles around opponents, but perhaps one way to offset the circle is with a straight-line attack?

The effects of the Premier League being as deep as ever

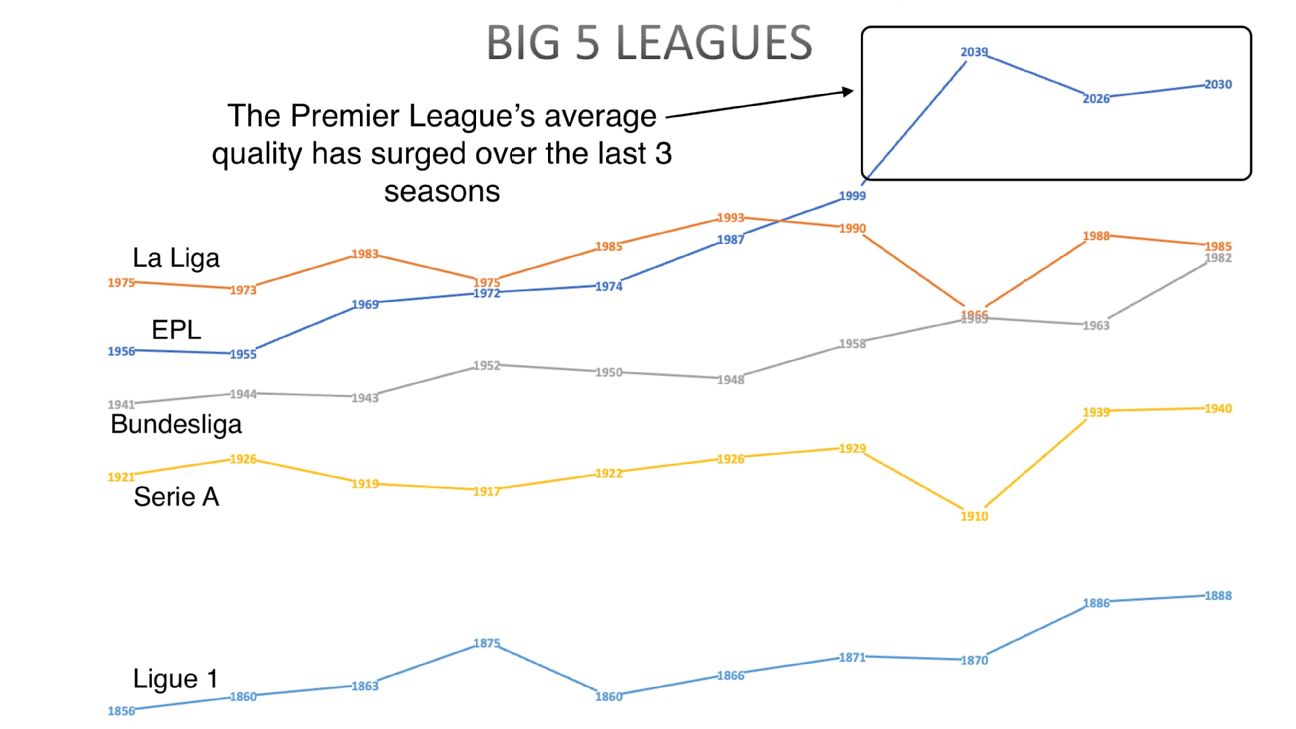

The chart shows Elo points (Y-axis) measured over time (X-axis). Source: EloFootball.com.

While we’re not entirely sure of the causes for this broader trend, it is perhaps telling to note the overwhelming Premier League presence on both of the lists above. Four of the top 10 teams on the coefficients list are from England, as are four of the 10 most improved. If we ignore the coefficients and look only at the nine top-50 teams that have improved their Elo ratings the most, four happen to be Premier League teams (Arsenal, Brighton, Manchester United and Newcastle United) that combined to spend nearly €700m on transfers over the past year.

The Premier League’s recent transfer spending explosion was bound to have some effects. Last year’s top four finishers (Manchester City, Liverpool, Tottenham Hotspur and Chelsea) have all seen their league results regress this season, while teams that spent money in a particularly smart fashion (or, by Manchester United’s standards, smarter than normal) have risen.

Of course, Chelsea spent more than anyone in England and have dropped more than anyone besides Liverpool. And for all of the vacuuming of talent Premier League teams have done over the past year, English teams haven’t exactly lit the world afire in the Champions League this season. As you see in the chart above, while the league has separated itself from the pack in terms of average quality, it isn’t really any better this season than it was in the past two.

Liverpool and Chelsea’s relative collapses, combined with healthy regression from Everton, Crystal Palace, Leeds United and continental competitors Tottenham and West Ham United, have offset the gains of other teams. And in the first leg of the Champions League round of 16, England’s four competitors combined got outscored 8-3 by Real Madrid, Borussia Dortmund, AC Milan and RB Leipzig, with three losses and a draw.

Chelsea did rebound to advance past Borussia Dortmund on Tuesday, and the Blues’ odds of reaching the Champions League final surged from 6% to 17%, but Tottenham offset that by bowing out meekly to an AC Milan team that has been in mediocre form. Maybe we’re bound for another All-English final that will provide an Elo bump and reinforce the league’s overall superiority. But as of now, the league hasn’t actually shown improvement with all of the money flying around, and it feels safe to say that regression by last year’s top four isn’t due entirely to Premier League quality and depth.

The most powerful clubs will respond, of course

We’ll explore the individual ways that top teams have regressed — as well as what it all might mean for next season and beyond — in a feature on Friday. But for now, it’s safe to assume that even if the possession game doesn’t work quite as well as it used to (which is still debatable), gravity will assert itself and the sport’s proven powers will remain powerful moving forward. The rich clubs will circle like vultures around the players most responsible for turnarounds at clubs such as Napoli and Lens, and the most powerful will remain the most powerful. This is doubly true if the World Cup, and the odd schedule, indeed played a role in this season’s oddities.

The oddities have been super fun, though. Napoli have been a revelation and could continue to make things messy for the powers in the Champions League, and underdog stories from the Union Berlins and Brightons of the world could still have pretty happy endings.

How happy? And how long will the stories last? We’ll see.