THE KANSAS CITY Chiefs’ team charter was in its descent when Nick Lowery looked out into the darkness and saw a long, glowing red ribbon down below — a massive line of cars on Interstate 29, backed up near the Kansas City airport. It resembled the final scene in “Field of Dreams.”

“I never in my life saw what I saw when we were flying home that night,” recalled the former Chiefs kicker, who played 18 years in the NFL on three different teams.

The Chiefs were returning home from a 1993 AFC divisional-playoff win over the Oilers in Houston, where a quarterback by the name of Joe Montana — in his first season with the team — had rallied them to a 28-20 victory with a 21-point fourth quarter. They were going to the conference championship for the first time since the NFL-AFL merger in 1970, prompting thousands of fans to form a giant welcoming committee at the airport.

That’s what a franchise quarterback can do: He can light up a city. A quarterback like Montana, who arrived with Hall of Fame credentials, can do it before he plays a down.

With a glittering résumé comes hope, and history tells us success-starved organizations will pay dearly for those commodities, regardless of the date on the birth certificate.

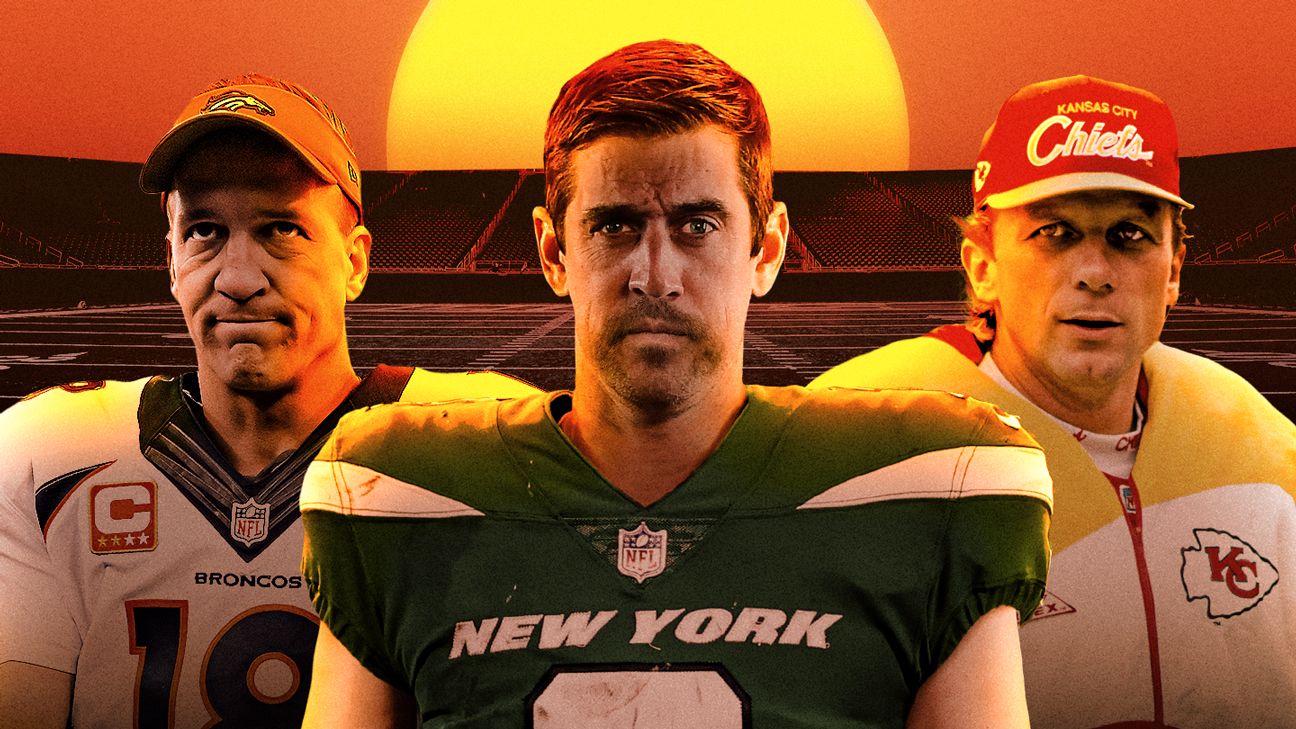

The Tampa Bay Buccaneers and Denver Broncos signed Tom Brady and Peyton Manning at 43 and 36, respectively. The Chiefs and New York Jets traded for Montana and Brett Favre at 37 and 39, respectively. They’re all members of the Pro Football Hall of Fame.

Whatever the reason — doubted, slighted or injured — they went from their supposed-to-be-forever team to a new city and a new way of doing things. Aaron Rodgers, who most certainly will join them in Canton someday, now is attempting the same late-career transition with the Jets after 18 seasons with the Green Bay Packers.

Ostensibly, Rodgers doesn’t need this. The 39-year-old’s legacy is secure, as was the case with the others, but he arrives harboring two chips — the one on his shoulder and the one he wants to win.

“All of us, that’s what makes us who we are — the competitiveness,” said Hall of Famer Warren Moon, who was 38 when he was traded to the Minnesota Vikings after 10 seasons with the Oilers and six with the CFL’s Edmonton Eskimos. “You’re not going to tell me when I should stop playing. I’m going to do that when I know I’m ready, and I’m going to show you.”

This is a story of show-and-tell. Moon showed ’em — they all did — but there’s also a truth to tell:

Change, even for the great ones, is hard.

LET’S TALK BEGINNINGS. Favre’s first day with the Jets in 2008 played out in broad daylight before starstruck eyes. With 10,500 fans watching — four times the usual crowd for training camp — he received a standing ovation as he walked out to Bruce Springsteen’s “Glory Days” for his first practice. With no offseason prep and virtually no classroom time to learn the plays — he didn’t arrive until early August — Favre launched rockets and was applauded for every completion. Yes, even the warmup tosses.

Brady’s unofficial debut with the Bucs happened in semi-privacy at school fields in the Tampa area. Eager to get started, he convened teammates throughout the spring for workouts, once incurring a complaint from the mayor for training by himself in a public park — a no-no during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020.

Manning’s earliest days with the Broncos in 2012 occurred in solitude, in a darkened film room and a lonely trainer’s room. Cramming the playbook and rehabbing his surgically repaired neck, he logged 12-hour days at the facility, sometimes ordering food delivery because he didn’t want to leave and disrupt his routine.

Montana’s start with the Chiefs was a joke. An all-time prankster, he tried to lighten the mood in the first team meeting by secretly setting off a stink bomb. The odor was so foul that coach Marty Schottenheimer called off the meeting and evacuated the room. By all accounts, he wasn’t happy.

Moon’s first drive to the Vikings’ facility was “a guessing game,” he recalled, because he didn’t know the route. (This was 1994, the pre-GPS days.) It was a stark reminder that, in many ways, he was starting over.

But nothing energizes a franchise like a quarterback who has been there, done that. He’s the super hero who arrives to save the day.

“It changes everything,” said former Jets general manager Mike Tannenbaum, who negotiated the Favre trade with the Packers. “The food tastes better. The grass looks greener. We felt like the moment he walked through the door, we had a shot to win a championship. Not talk about it, not dream about it, but like, ‘OK, we’ve got freaking Brett Favre. Let’s go!'”

Favre, feted by New York mayor Michael Bloomberg before he played a game, led the Jets to an 8-3 start in 2008, fueling Super Bowl dreams. But he tore a biceps tendon in his throwing arm and they missed the playoffs at 9-7 even though he gutted it out and didn’t miss a game. Favre retired for the second time in 11 months following the 2008 season — but this one didn’t last, either. His next team got what the Jets wanted. A healthy Favre led the Vikings on a playoff run in 2009.

The others — Brady, Manning, Montana and Moon — led their new teams to the playoffs in the first season. Brady took it further, winning the Super Bowl. So did Manning, but it didn’t happen until his fourth and final season in Denver.

Before the confetti, there was adversity, especially for Manning.

He was released by the Indianapolis Colts after sitting out the 2011 season with a significant neck injury, and there was no guarantee he’d recapture his vintage form. Former Broncos coach John Fox said Manning had to “reteach himself” how to pass a football. Because of nerve damage, Manning “didn’t know where his arm was” when he reached back to throw, according to Fox.

To this day, Fox is awed by what Manning had to overcome. He believes the injury, coupled with the pink slip from the Colts, provided premium fuel.

“In Peyton’s case, I don’t think he ever expected the Colts to cut him,” Fox said. “He’s very respectful and never says a bad word about the Colts organization, but he had a purpose now — and that’s huge. That’s a big thing with these elite athletes.”

Montana endured something similar with the San Francisco 49ers. He missed the 1991 season with an elbow injury, then was the backup to Steve Young in 1992. Essentially, he missed two straight years, finding himself in limbo after four Super Bowl championships with the 49ers.

No one would’ve questioned his greatness if he had opted for a golden parachute, but he surprised many, including the 49ers, by pursuing the Kansas City opportunity.

“I think he had experienced the pain of sitting behind Steve Young, not feeling like he was appreciated,” said Lowery, who sat with Montana in first class on team flights — the privilege of being the two oldest players on the Chiefs. “Joe’s mind and heart went to, ‘I’m going to get those f—ers.'”

Moon was coming off his sixth consecutive Pro Bowl with the Oilers when he got traded to Minnesota in 1994 (a few months after losing to Montana in the playoffs). He understood the financial implications — the salary cap was in its infancy — but he felt wronged.

And he spoke up.

“I told the GM at the time, Floyd Reese, ‘You know what? I’m not done yet. I understand why you’re doing this, but I think you’re making a mistake,'” Moon said. “The next time we played, I saw him after the game — we beat them — and I told him, ‘I told you so.’ He just laughed.”

Moon, who got a late start in the NFL because of his CFL career where he won five Grey Cups, made two more Pro Bowls with the Vikings. He proved his point.

Brady’s exit from the New England Patriots was presented by both sides as a mutual parting. His contract expired, he became a free agent and chose the Bucs. They hadn’t made the playoffs in 12 years, but he saw them as a stock on the rise.

The first year had a storybook ending, as Brady ended up with the Lombardi Trophy in his arms for the seventh time in his career, but there was tension along the way. People forget the Bucs were 7-5, in danger of missing the playoffs.

Brady, after 20 years in the Patriots’ system, wasn’t comfortable in coach Bruce Arians’ offense. They adjusted on the fly, using their bye week to make the offense more Brady-friendly. The result: The Bucs didn’t lose another game the rest of the season.

“Having to learn a new offense in your 18th, 19th year, it’s almost impossible because you have to unlearn your old offense,” Manning said in a recent episode of “The Pat McAfee Show.” “You saw it with Brady.

“He goes to Tampa and they’re making him learn some different language. All of a sudden … they’re like, ‘Maybe we should just call the plays Tom used to run in New England.’ OK, OK, let’s do that. Boom! They go to the Super Bowl.”

Reflecting on his Denver offense, Manning said they combined playbooks — his personal playbook and that of the Broncos’ — to create a hybrid. During the offseason transition, Fox hired former longtime Colts offensive coordinator Tom Moore — a Manning guru, if you will — to teach Manning’s system to the Denver coaches.

It was a historic success, as the Broncos set the league record for most points in a season (606) in 2013.

From an X’s and O’s standpoint, Moon had it tougher than anyone. In Houston, he directed the run ‘n’ shoot, a four-receiver attack with lots of option routes and motion — an offense rarely used in the NFL. In Minnesota, he had to become a traditional dropback passer, which meant learning new footwork.

It was like learning how to read from sheet music after years of playing by ear, but Moon worked on it for countless hours after practice and eventually mastered it, leading the league in completions in 1995 at age 39.

Time was the enemy for Favre and the Jets, who didn’t make the trade until two weeks into training camp. Tannenbaum was stressed, knowing they had to cram a few months of work into three weeks.

The former GM, who took a private jet to Favre’s home in Hattiesburg, Mississippi, was anxious as he waited for Favre and his wife to pack their suitcases for the trip to New York. Let’s just say Favre wasn’t in hurry-up mode, and Tannenbaum could almost hear the clock ticking toward Week 1.

“The whole thing was surreal,” said Tannenbaum, now an ESPN analyst. “I felt a sense of relief, to be candid, when he and Deanna were on the plane and the door closed. I felt like, ‘OK, I did my job.’ I slept great on the plane.”

Instead of force-feeding their system to Favre, the Jets adjusted as much as they could to suit him. When all else failed, he did what he did best — he improvised. Players said Favre was famous for making up plays in the huddle.

PAUL HACKETT OBSERVED from the sideline last week, chatting with Jets owner Woody Johnson as they watched the team’s prized acquisition — Rodgers — practice under the guidance of Paul’s son, offensive coordinator Nathaniel Hackett.

Talk about a full-circle moment.

Thirty years ago, it was Nathaniel — only 13 — who studied his dad as he coached Montana through his initial paces at Chiefs practice. Paul was hired that year, 1993, as the offensive coordinator.

The situations are strikingly parallel. Years before joining the Chiefs, Paul was Montana’s quarterbacks coach for three years in San Francisco. Paul’s presence in Kansas City was one of the factors that convinced Montana it was the right place.

Similarly, Nathaniel was Rodgers’ coordinator for three years in Green Bay, where they forged a tight bond. That relationship, Rodgers said, was a primary reason for him agreeing to the trade.

Nathaniel said he has discussed the Montana years with his now-retired dad, 75, hoping to cull nuggets that can apply to the present. Rodgers, too, has talked to the elder Hackett about it.

“I was lucky to be just a young kid when that happened with Joe and my father, and I thought it was a great experience for both of them,” Nathaniel said. “Both of them had come into an organization that was starved to move forward in their progression, and I think my dad and Joe — it was great because they had been in the same system. A lot of that is the same for Aaron and I.”

Rodgers’ background in Hackett’s version of the West Coast offense should make for a seamless transition from a schematic standpoint. It did for Montana. As Lowery recalled, “Joe, in practice, was like watching the conductor of a New York symphony.” Unfortunately, Montana suffered a concussion in the 1993 AFC Championship Game and the Chiefs lost to the Buffalo Bills, 30-13.

Not every legendary quarterback gets a happy ending. Some don’t even get a happy beginning on their second team. The most infamous examples are Joe Namath and Johnny Unitas, iconic players with the Jets and Baltimore Colts, respectively, who headed to the West Coast looking for a final fling.

Unitas, 40, looked out of place with the San Diego Chargers in 1973 and played poorly in four starts. Namath, 34, got the same number of starts with the Los Angeles Rams and the results were almost identical in 1977. Those golden right arms had three touchdown passes apiece.

Looking back, Namath said he underestimated the late career change, calling it “a very difficult transition.” He loved the Jets — he was the face of the franchise — but they had a new coach and a young roster. Not interested in a rebuild, he requested a trade. It was tough. Even calling plays was hard; he kept reverting to his old plays with the Jets.

No one expects this to happen to Rodgers, 39, who seemingly has everything he needs. He’s reunited with an old coach, a handful of former Green Bay teammates and a system that helped him win the NFL MVP in 2020 and 2021.

Manning expects Rodgers to succeed because of his familiarity with the offense, saying, “He’s going to be able to play so much faster.”

Bucs coach Todd Bowles, the defensive coordinator in Brady’s first season in Tampa, said, “I can’t speak for the Jets and Aaron. I can speak on what Tom did for us and we won a Super Bowl. … Aaron is so smart. He can see things on the field that only the great ones can see. He’s an outstanding player, he really is.”

And a motivated player.

A contentious divorce from the Packers has provided additional ammunition for Rodgers, according to those who know him. They say he’s rejuvenated, eager to prove last season — a down year by his standards — was a fluke.

“They’re getting a pissed off Aaron Rodgers, which is exactly the Aaron Rodgers you want,” said former Jets coach Eric Mangini, who coached Favre in 2008. “When he was pissed off about Jordan Love, he won the MVP. When he was pissed off about his contract, he won the MVP. When Jordan Love wasn’t an issue and the contract was taken care of, not as great. Now he’s pissed off. It’s perfect.”

The stakes are enormous for the Jets, who, after 12 consecutive non-playoff seasons, have shifted into win-now mode. The owner is paying nearly $60 million in guarantees for Rodgers, who will earn a total of $108 million if he plays a second year. This is the same owner — Johnson — who fired Mangini when things went awry at the end of Favre’s one-year run.

If anyone can appreciate the pressure on coach Robert Saleh, it’s Mangini.

“I would say embrace it because it’s real and it’s not going away,” Mangini said. “It better work. If it doesn’t, odds are someone else will try to make it work next year.”