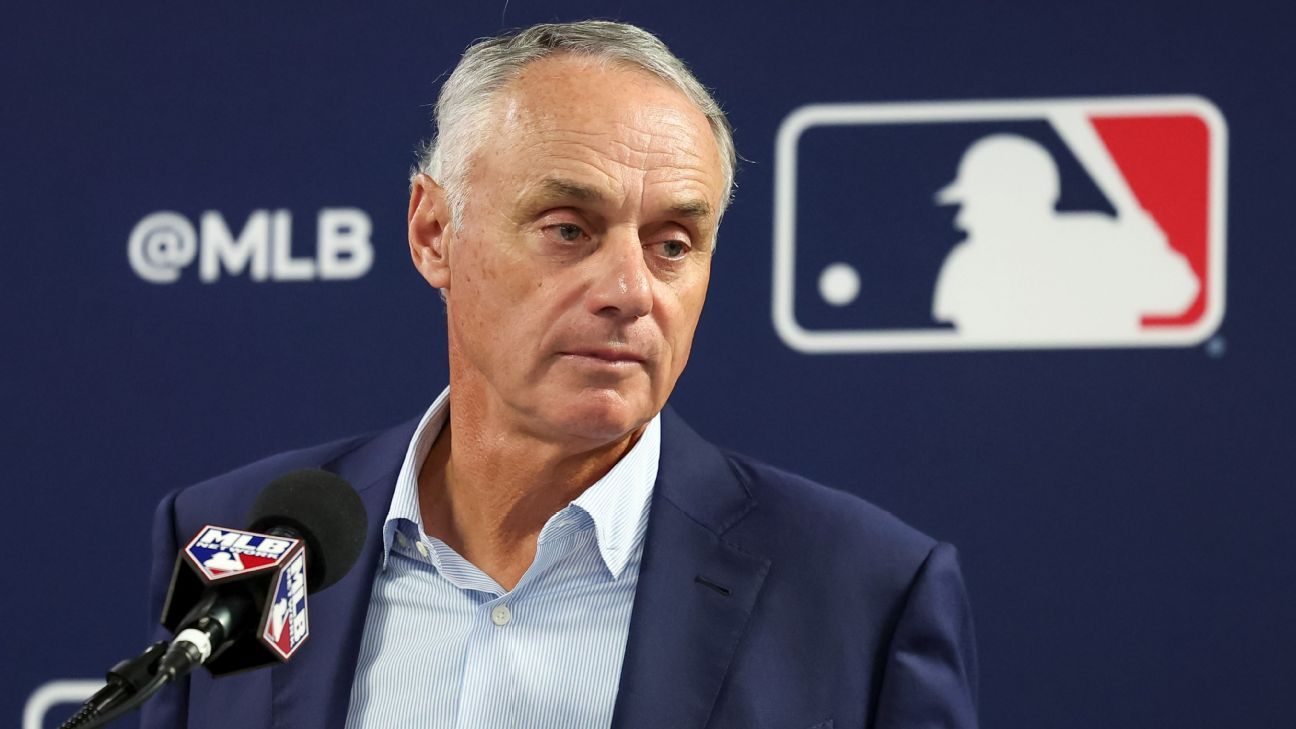

Rob Manfred announced his 2029 retirement as commissioner of Major League Baseball on Thursday in the most Rob Manfred of ways. In an answer to a question about the awarding of future All-Star Games, Manfred made an offhand comment about his limited time remaining in the job. A follow-up elicited more clarity: He plans to step down upon the expiration of the new contract owners awarded him this past July.

The odd timing — and odder setting, at a general media availability in Florida — was on brand for Manfred, who took over from Bud Selig in 2015. His public handling of some of the crises of his tenure as commissioner — the Houston Astros cheating scandal, the Oakland A’s move, the 2021-22 lockout — have turned into crises themselves. Appealing to fans, of course, isn’t a prerequisite for the modern commissioner. Manfred’s job is to serve 30 billionaires, and in those team owners’ eyes, his tenure has been a success.

In his first decade as commissioner, Manfred oversaw an increase in industry revenue and a significant jump in franchise value, two factors that owners care about much more than fans do. Sometimes he can serve both, as he did with the 2023 implementation of a pitch clock, a rousing success that also coincided with a nearly 10% increase in attendance. But over the past 10 years, he has made abundantly clear the party for which he works, and the owners believed in him enough to offer an extension for his $25 million-a-year job.

Which sets up a fascinating half-decade ahead as Manfred balances his bosses’ whims and the legacy he wants to leave. How Manfred handles these remaining years will shape history’s view of him. For all of its warts, baseball is in a good, if tenuous, place. Incredible athletes populate the game. Business keeps booming. And, as ever, one misstep could jeopardize that momentum.

His most immediate order of business is figuring out how to weather the near-collapse of the company that handles local-TV broadcasts for about half the teams in the sport. It also offers Manfred his greatest opportunity yet to simultaneously satisfy fans and owners. Television blackouts have prevented tens of millions of fans from watching the sport, a Faustian bargain that traded the game’s long-term health for owners’ short-term profit. Manfred has said he wants to rid the game of blackouts and intends to do so by packaging the TV broadcasts of the affected teams and, eventually, bringing all 30 under the service’s umbrella.

Navigating such treacherous terrain takes a nimble operator, and Manfred always has been more Doberman than Dachshund. He faces immense pushback from big-money teams that own their own regional sports networks — the New York Yankees, New York Mets and Boston Red Sox among them — and a package with half of MLB’s teams would be the ultimate half-measure that could deepen the game’s already-widening chasm between have and have-not. Finding an elegant solution would go a long way toward future-proofing MLB.

Just as concerning, if not more so, is the prospect of another lengthy work stoppage, in service of owners trying to squeeze every last penny out of a new collective-bargaining agreement in 2026. The last collective-bargaining talks saw MLB lock out the players for 99 days and narrowly avoid devastating the sport. The complications of the commissionership — placating a coterie of wealthy owners with factions whose loyalties could be imperiled by the outcome of the media-rights deal — are laid bare during collective bargaining. Compounding the inherent difficulty of the economic negotiations that define every basic agreement are additional elements Manfred is seeking, all of which the MLB Players Association must approve.

Manfred said Thursday he wants two expansion cities to be named by the end of his tenure. Getting the $2 billion-plus in expansion fees for each team necessitates a deal with the union. Further, one of Manfred’s chief goals over the next half-decade — continuing to increase MLB’s reach, in part through international and special-event games — requires buy-in from a group of players that regard him with, at best, begrudging respect and, at worst, contempt.

Bettering the on-field product remains of great import, too. The pitch clock made baseball a better game, shaving about 30 minutes off every game by simply cutting out dead time. MLB’s newest innovation, a computerized zone that brings uniformity to ball-and-strike calls, could arrive as soon as 2025. Whether the league goes fully automated or implements a challenge system, change of any variety — even progress — rankles a segment of baseball fans and adds another pothole on the road to retirement.

Of course, despite Manfred’s intentions now — we know now that when he signed his 2024 extension, he’d suggested to owners that this was his last term — all of this speculation might well be for naught. In December 2006, Manfred’s predecessor, Bud Selig, said he would retire when his contract expired in 2009. Barely a year after his announcement, he signed a new deal through 2012 and pegged his retirement to its conclusion. At the behest of owners, Selig reneged again, signing up for two more years before backing Manfred as his heir to one of the most powerful seats in sports.

Five years out, there is no clear successor to Manfred. Owners could coalesce around an internal candidate at the commissioner’s office. They could tab a team president. They could look externally. Two owners Thursday said it’s far too early to speculate. Too much can happen over the next half-decade.

Manfred’s tenure so far has seen more wins than his detractors care to acknowledge. These next five years, though, bring the opportunity to burnish that legacy. A commissioner not angling for a new contract can put aside the politics and mollifying inherent in the job and prioritize the future of the game, not the owners’ investments. He could fix an international signing system that sees 12-year-olds agreeing to deals and others lying about their ages to make them more attractive to teams. He could help repair a broken youth program that sends pitchers into professional baseball with scars already on their elbows. He could incentivize teams to spend earlier in free agency and prevent another slog of an offseason like the current one bleeding into spring training.

These are novel thoughts, and perhaps naïve ones, too, because Rob Manfred is still here due in large part to his success in making rich men richer. He is ownership’s attack dog and flak jacket. Manfred has said time and again that he is commissioner because he loves the game. As the clock ticks on the tenure of Major League Baseball’s 10th commissioner, he has the chance to prove it unequivocally.