Sign up for notifications to the latest Insight features via the BBC Sport app and read the latest in the series here.

Eyes blinded by a blend of floodlights and blurry bodywork. Eardrums drenched in the whirring neighs of 1,000 mechanical horses. Nostrils stained with the stench of burning brake ducts. Spine rattling to-and-fro against the rhythms of the road. Limbs and neck wrestling relentlessly with immense gravitational force.

Firing a Formula 1 car around a racetrack at top speed is one of the most intense sensory experiences a human can undergo.

During races, drivers can suffer motion sickness, light-headedness and vision glitches. They can lose up to 3kg in under two hours while at the wheel.

With the success and failure of their split-second decisions laid bare for the world to witness, a driver’s existence can be isolating as well as physically draining.

But an F1 driver is never racing entirely alone.

They are accompanied, always, by the guidance of a softly-spoken ally at the other end of the team radio system, aiming to maximise the driver’s result at race end.

That voice belongs to the race engineer.

Weather changes, tyre wear, gear shift advice and details about rivals’ weaknesses are among the technical information passed from the race engineer to the driver. But the engineer must also harness their more human-centred skills, suppressing the driver’s concerns and emotions so they are free to operate entirely in the present.

Key highlights make it to TV broadcasts, but most of this dialogue goes unheard by fans.

Given the amount of time the driver and race engineer spend in each other’s company, and the faith they must collectively construct, their relationship is one of the most intimate in elite sport.

“What you are trying to do is to take a lot of cerebral thinking away from the driver so that he can just be in the moment, focusing on the next corner and maximising the potential of the car,” says McLaren’s Tom Stallard, a race engineer who first joined the team in 2008 and currently works with Australian hot prospect Oscar Piastri.

“We are the translator that bridges that gap between the technical department and the driver – we find the best way to get the information between those two parties.”

In turn, the driver must have total confidence in the competence and character of his pit wall connection.

There is almost always at least one generation between a driver and his race engineer. They often come from completely different parts of the world and do not share a first language. A big effort to understand each other’s backgrounds, personalities and motivations is key to building a successful relationship.

“I always try to meet a new driver in a non-professional environment – at a restaurant or wherever else we are disconnected from Formula 1, to understand his personal side,” says Jorn Becker, who spent eight years as a race engineer for Sauber until a recent change of roles with the team.

“We spend a couple of hours together, just talking about normal things in life – hobbies, his family, his education – to understand his culture.

“At the same time I am observing his reactions on a human level.

“You maybe even have to adapt your own personality to deal with the driver you get.

“Probably the most important part of [being] a race engineer is the human aspect. You need a good level of emotional intelligence and empathy.”

Stallard, who has worked with Carlos Sainz, Stoffel Vandoorne, Daniel Ricciardo and 2009 world champion Jenson Button in his time with McLaren, agrees the formative days with a new driver are crucial.

“I am a big believer in the importance of building that social connection,” he says. “You don’t necessarily have to go out – just hang out together, ask questions and tell stories.

“With Oscar, we developed that relationship by spending time together – a couple of times out for meals and stuff, but a lot of it just at the factory having coffees – and talking through racing situations from early in our careers.

“We had a lot of conversations around things we messed up in the past in order to share some of those painful F1 life lessons.

“That is a way of adding a real-life, humorous element to preparation – because when you look back years on, you can laugh at your mistakes.”

Not every driver-engineer pairing has a full winter of preparation to develop an understanding, though.

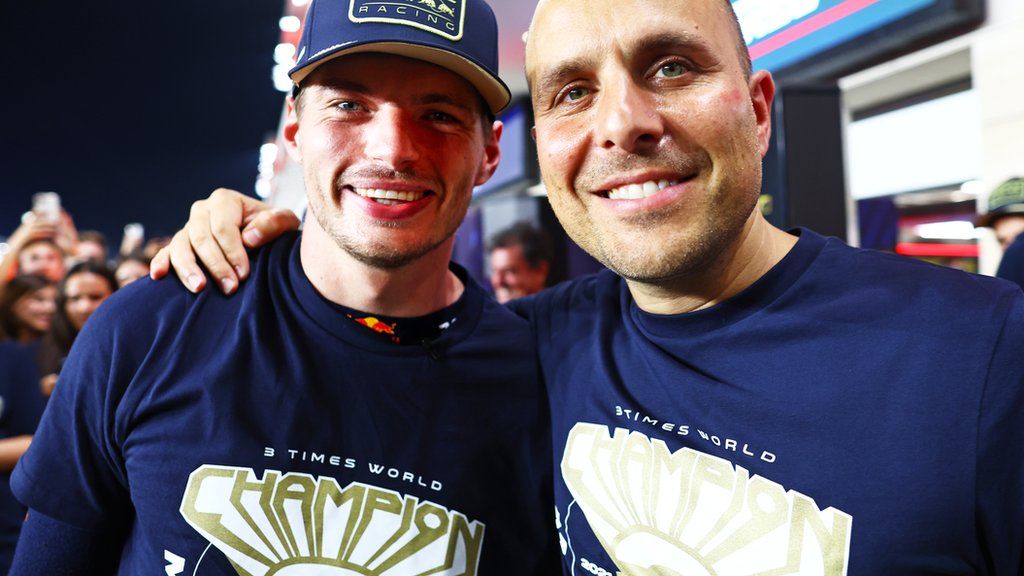

When now-triple world champion Max Verstappen was first promoted to the Red Bull team mid-season in 2016, race engineer Gianpiero Lambiase was tasked with moulding an 18-year-old possessing both supreme talent and a frank demeanour with only a few days’ notice.

“I had experience working with multiple drivers before Max, and that was one of the biggest helps in terms of hitting the ground running with him,” Lambiase explains. “I think if I would have been a newbie to my role – I won’t quite say he would have eaten me alive, but I’m not sure he would have had that respect for a junior engineer.”

Their relationship was an immediate success. Verstappen became the youngest race winner in F1 history, finishing first on his debut at the Spanish Grand Prix. But, generally, the first few years of Lambiase and Verstappen’s partnership were spent chasing perennial frontrunners Mercedes.

“Max learned some really harsh lessons in the two or three years before 2021,” says Lambiase.

“His racecraft really was something that we focused on, making sure we were just picking up points when it wasn’t possible to win a race.

“We were concentrating on building his consistency, needing to be finishing every race, maybe not putting himself in a situation where he can end up in a 50/50 accident with another driver.”

That spectre of an accident is a fundamental part of the relationship between the two.

The race engineer is responsible for the set-up of the driver’s car, alerts them to incidents and on-track traffic, and monitors their temperament.

To an extent, the driver puts their life in the hands of their race engineer whenever they take to the track.

“I feel very aware of safety at the race start, but in general I don’t dwell on that more than a driver does,” Stallard says. “You realise drivers are much more scared of dishonour.

“They are often much more worried about the shame of damaging a very expensive car and being out of the race than they are about the personal injury risk. It is more fear of not doing enough than doing too much and something terrible happening.

“Those moments [when crashes happen] are difficult because it is your friend in the car. It is not just a colleague – you don’t work with someone that closely and not become friends.

“At a certain point in an accident, all of the lines of data go vertical. You know something bad has happened, but a small spin and a crash into the wall look incredibly similar.

“You don’t really know what happened. It is very easy to ask the wrong question like, ‘Is the car OK?’. That sounds odd to someone watching on TV, who, before they hear that, has seen very clearly that the car has gone into a wall at 200kph. But the good thing is drivers are quite understanding.”

During his debut season in 2022, China’s Zhou Guanyu suffered one of modern racing’s most harrowing crashes.

Multiple cars made contact just after the start at Silverstone, sending Zhou’s Sauber tumbling upside down, hurtling across the tarmac and through the gravel at high speed. Upon impact, the car flipped over the barrier and landed on its side. Until he was extracted from the car around 20 minutes later with no significant injuries, many feared the worst.

On the Swiss team’s pit wall, desperately waiting for news, was Becker.

“That was definitely the biggest accident I experienced with a driver,” the German recalls.

“We immediately lost telemetry to the car, so there was no communication to him. And we did not receive any information from race control because they did not know how he was either. It was 15 minutes without any information, which was very, very difficult.

“But you remind yourself that you have to be professional. I pushed hard to keep it on the calm level, because if I start to get worked up as a leader in the team, then everything goes in the wrong direction.”

Piastri’s accomplished rookie season, in which he secured a ninth-place finish in the drivers’ championship, was achieved in spite of a dreadful start to the year for his McLaren team, who were way off the pace of the leaders.

His ability to control his emotions during that time made life easier for Stallard.

“The role of a driver in a team, even a rookie, is a significant leadership position because there are only two people that drive the car,” Stallard says.

“Leadership from a driver can be a lot of different things – it is not always standing up in front of hundreds of people and orating to the entire organisation. A lot of it is in the debrief over the intercom, the feedback about performance, or the way they present themselves in the car.

“I don’t think Oscar realised he was doing it, but he was leading just by being in the team, taking stuff on himself and not apportioning blame.

“He could have been really difficult, but the leadership and calmness he showed in that period was one of the instrumental factors in keeping the team in the right place and turning around performance.”

During his time working with current Ferrari driver Charles Leclerc at Sauber, Becker also experienced the rapid development of a young driver who many believe is a future world champion in waiting.

“When he was testing for the first time for us, we have a reference data set – a baseline – where we can measure how quickly he can adapt to F1, and during this test we could all already recognise that Charles was very special,” Becker explains.

“His way of working was special too.

During testing, he always had a small black book in the car. And after each run he made some notes to remember – the most important details. And then in the debrief later on he was referring to the information he wrote down during the session, which is quite impressive.

“He had a very academic approach. Some outstanding drivers are not interested in the technical side, and then they converge to a certain level where they do not improve any more. They just reach the limit of their talents. But the top guys find this extra step by being very good in car development and set-up.”

As well as evaluating the pace of car and driver at the end of a race weekend, engineers review how they themselves have performed over the airwaves.

“I actually practise [managing adrenaline],” says Becker. “I usually do a race replay where I listen to all the radio conversations, which is very chaotic, and try to practise being very calm and training my voice to have a consistent volume, not speak too fast, and so on.”

Prior to dedicating himself to engineering full-time, Stallard was an accomplished rower who competed for Cambridge in the Boat Race and won a silver medal with Team GB at the 2008 Olympic Games in Beijing.

“I think I have always been quite good at handling pressure,” he says. “One of the things I was always very aware of as a rower is that you need the crew to work. If you create stress for the other athletes, the crew doesn’t work. The same is true of an F1 team.

“Increasingly you realise that it is the human side where most of the competitive edges come from in F1. You realise it is all about the people.”

Sometimes, though, tension between driver and race engineer can spill over in the most high-pressure moments.

Now in his ninth season working with Verstappen, having won the championship in each of the past three seasons, Lambiase’s voice is a staple of every F1 broadcast and has become recognisable to fans all around the world.

The pair’s success does not mean their communications are entirely straightforward.

At the Belgian Grand Prix in 2023, Verstappen used expletives while lambasting the strategy the team opted for during qualifying. Lambiase quashed the criticism with a sarcastic retort inviting Verstappen to do his job as well as driving the car.

In Brazil the previous year, Verstappen had refused an order from Lambiase to allow team-mate Sergio Perez to pass him before the finish line.

“I think it is inevitable in any relationship that there are disagreements,” Lambiase says.

“The first port of call is acceptance of that. Secondly, you need to have faith in each other that it is for the greater good rather than there being any kind of malicious undertone. That is at the core of the relationship.

“As an engineer, I need to understand that ultimately Max is in the hot seat, not me.

“So while we are all working in a pressurised environment, the driver is at a level well beyond that.

“As an older citizen I would like to think I am mature enough to step back and let him vent when necessary, but to also make him understand why decisions are being made.

“If I was a yes man, I would have been gone long ago. We have just got that honesty in the relationship between us that we can be blunt and straight-talking when needed.”

As well as coping with adrenaline themselves, race engineers must manage the pressure on their racers.

The 2021 campaign was arguably the most intense in F1’s 74-year history. After an acrimonious year marked by heavy collisions between the pair on track and serial sparring between their respective team principals in the paddock, Verstappen and rival Lewis Hamilton’s title fight came down to the wire at the season finale in Abu Dhabi.

There the Dutchman secured his maiden championship by overtaking Hamilton on the final lap following an incorrect restart decision by the race director, sealing glory with the eyes of the world on him.

“I wouldn’t want to repeat 2021 in a hurry,” Lambiase says. “It was incredibly competitive on and off the track [but] sometimes I think it went beyond the realms of sport.

“In terms of taking that pressure away from Max, I tried to stress with everybody here that we continued as normal. We treated every race as a single event rather than trying to look too far down the line at what could be.”

Though fighting at the front presents a huge challenge, arguably the biggest test of a race engineer’s ability comes when their driver is struggling.

During a two-year stint working alongside Stallard at McLaren, Ricciardo – the ebullient Australian, who became a fan favourite in Netflix’s documentary series Drive to Survive – struggled to find form, lagging behind younger team-mate Lando Norris. He was eventually dropped a year before his contract was due to end.

“Daniel joined the team during the second Covid lockdown,” Stallard remembers. “That was quite challenging because he was based in Los Angeles and we had to [get to know each other] over video call. We could cover the technical stuff, but we missed out on quite a lot of the social interaction.

“Ideally you know the driver well enough to allow quite a lot of unheard, non-verbal communication to happen between you.

“A driver struggling is a very tricky situation in a sport where there is virtually no training. You go away, lick your wounds, try to understand what happened and what you need to do differently, then come back with a new plan and try again.

“When the team decided that they were going to get Oscar instead of Daniel, it took quite a long time for me to process that, because I was so deep into the process of working with him and improving with him all the time.

“It was frustrating that it ended before we solved the puzzle. I never really lost heart. I never felt like, ‘Oh this isn’t going to work out’.

“This is going to sound weird in a way, but I am quite proud of the work we did with Daniel. We all worked pretty hard on that, including him too.

“We are still very good friends now, I see him at all the tracks. It would be easy to imagine that the opposite would be true.

“Partly it is a reflection on his character, and I would like to think a reflection of the strong collaboration between us, too.”

No matter how long a driver and race engineer have worked together, and how close they become, those partings of ways are inevitable in Formula 1.

“The season finale in Abu Dhabi usually feels a bit strange if you know the driver will not continue with you. It is always the end of a chapter,” Becker says.

“Some chapters are very short, like with Charles, but with Antonio [Giovinazzi] the relationship was three seasons. So it feels a bit sad.

“Usually the driver will give me a little present, a race helmet or whatever, which is very nice. And then the real farewell is at the Christmas party, usually a week after the finale. That is the last moment together, where we have dinner and a drink. We move on, but I am still in contact with most of my drivers.”

For Stallard, saying farewell is an opportunity for the friendship to continue in a different, more combative form.

“Yeah, it does definitely [feel like a loss], but equally you want the best for them,” he says. “You also want to beat them [in their new team], because there is nothing more fun than beating your mates.”

In some cases though, the idea of starting afresh following the end of such a deep connection doesn’t appeal any more.

“I honestly see Max as a younger brother,” Lambiase says. “We can talk about anything and anyone at any time. We’re at the point where we just felt completely relaxed and at ease with each other.

“Maybe I am speaking out of turn, but I don’t think I would have any interest in working with another driver now.

“Having had the success that we have enjoyed together with Max, working with one of the greatest talents that the sport has ever seen, I don’t think it would be fair on another driver, from their perspective or mine, to try and replicate what we have achieved with Max.”

In Formula 1, as in all our lives, the magic of the most special relationships will always remain utterly unique.