Editor’s Note: This story is being republished following O.J. Simpson’s death on April 10, 2024. After this article was originally published on Dec. 12, 2019, Tom Kriessman changed his story and told ESPN that he sold his copy of Simpson’s Heisman Trophy to a collector in Reno, Nevada, the previous year. Here is the update to this ever-changing tale.

On June 17, 1994, as O.J. Simpson’s infamous low-speed Ford Bronco chase captivated the country, crowds began to gather along the highways of Los Angeles and seemingly every locale around the city associated with Simpson.

At USC’s Heritage Hall, Los Angeles Police Department officers arrived and requested that Simpson’s 1968 Heisman Trophy and game-worn jersey be removed from the lobby for safety’s sake.

It was a midsummer Friday afternoon, and only one football staffer was in the office. The task fell to Jeff Kearin, a graduate assistant coach for the Trojans, who took the statue and jersey from their display case and locked them up for safekeeping.

When Monday arrived and the furor on campus had calmed down, the Heisman and jersey were returned to their proper place in the Heritage Hall lobby.

Eight days later, they were removed again. This time by burglars.

With the world — and local law enforcement — transfixed by Simpson’s arrest, no one paid much attention to a missing trophy. That’s how it ended up buried in a backyard and later traveling the streets of L.A.

Until it was mysteriously returned to USC more than 20 years later.

The two most infamous versions of the sport’s most famous trophy currently sit 2,700 miles apart. The trophy that was once believed to be lost forever is now back at USC, in nearly the same spot from which it was snatched away in 1994. Meanwhile, the trophy that had been the centerpiece of Simpson’s home and then the centerpiece of a sprawling legal battle might never be seen again, stuffed away in a Pennsylvania bank vault.

The men behind the strange-but-true odysseys of those Heisman statues over the past quarter of a century are as disparate as their current locations. One, a man with a lengthy rap sheet who claims to have purchased USC’s stolen Heisman for $600 and a used car, the other a sheet-metal wholesaler from Philadelphia who purchased Simpson’s copy at auction for more than a quarter of a million dollars.

One man had his copy for nearly 20 years, stashing it in various Los Angeles apartments while in between jail stints until he was so eager to get rid of it that he returned it to USC in the hopes of getting a reward. The other bragged when he won the auction that he bought it because, he said, “You always have to keep impressing your girl!” but has tired of talking about his prize and won’t show it to anyone.

The trophies might not be cursed, but they don’t seem to bring much joy to anyone who comes into their possession these days.

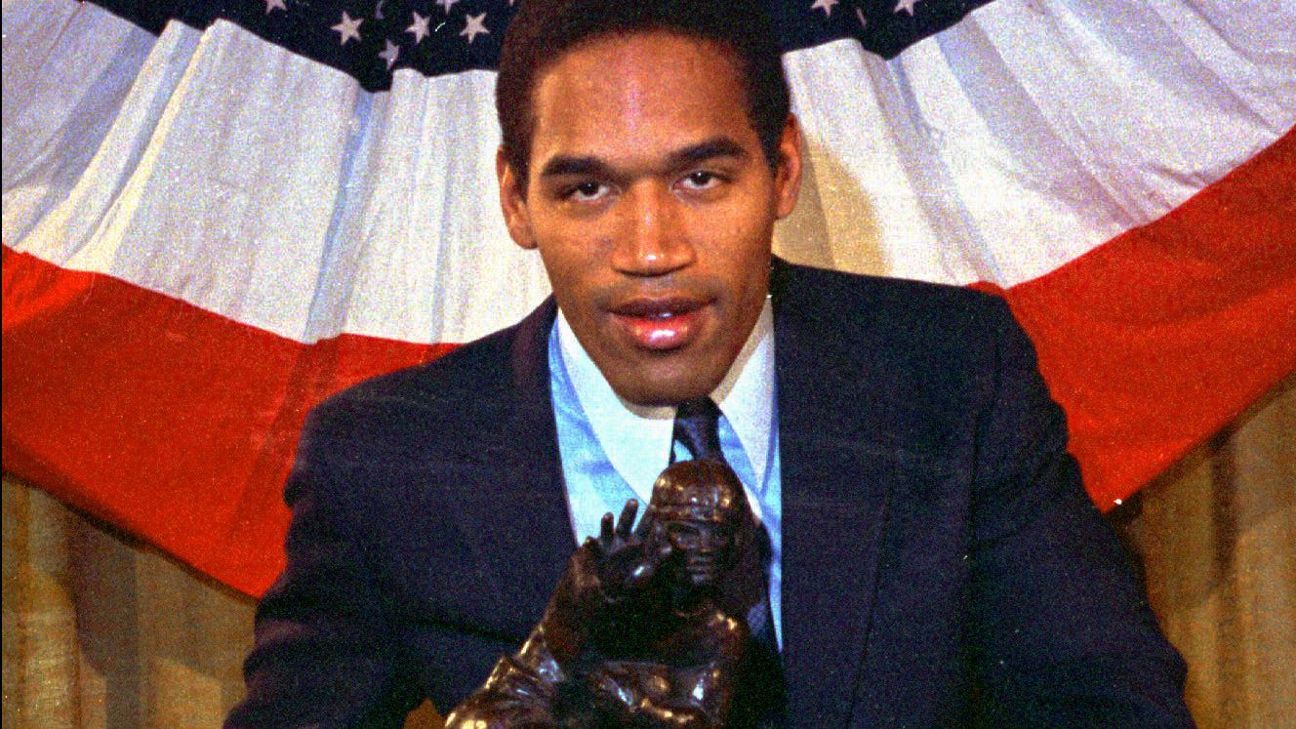

Fifty-six years ago, O.J. Simpson first gripped his prize for being, as is engraved on the brass plaque, “the outstanding college football player in the United States for 1968.” It was awarded on Dec. 4 by New York’s Downtown Athletic Club, or, as it is engraved on that same Heisman plaque, the “Downtown Atletic Club,” missing an “h.”

But the statue Simpson held while being interviewed by Howard Cosell wasn’t the only Heisman handed out that day. Only two years earlier, the Downtown Athletic Club had started presenting a pair of trophies each year, one to the athlete and one to his school, inspired to do so after 1966 winner Steve Spurrier handed over his Heisman to the University of Florida, saying it should be enjoyed by more than just himself.

Over the next couple of decades, Simpson’s edition of the ’68 trophy — let’s call it Heisman No. 1 — followed him through various homes until 1977, when he moved into a new, garden-draped estate at 360 North Rockingham Ave. in Brentwood, California. Heisman No. 1 was featured prominently in the place he called simply “Rockingham,” displayed in a glass trophy case in the main room of the house along with the No. 32 USC jersey he’d worn in his last collegiate game. Simpson loved the shock and awe value of showing the trophy to first-time Rockingham visitors.

Only 15 miles to the west, USC’s ’68 trophy — let’s call it Heisman No. 2 — had settled into its own eye-catching location in the lobby of Heritage Hall. The bustling hub of Trojans athletics sits in the middle of campus and in the middle of Los Angeles, less than 5 miles south of L.A. City Hall. It is designed to be a busy, open space that welcomes students, staff, recruits, fans and any other passersby to peruse the school’s astonishing collection of trophies, including a football stockpile of 11 national championships, 25 Rose Bowl victories and six Heisman Trophies. All due respect to Marcus Allen, Mike Garrett, Charles White, Carson Palmer, Matt Leinart and, before it was removed, Reggie Bush, they have never been Heritage Hall’s Heisman headliners. As Simpson ran into the Pro Football Hall of Fame, TV commercials and Hollywood films, his trophy became far and away the biggest draw. By the early 1990s, the USC Heismans — then four — were moved into standalone display cases that lined the Heritage Hall lobby like bronzed sentinels.

On June 12, 1994, it all changed. That’s the night Nicole Brown Simpson and Ronald Goldman were murdered. The Bronco chase happened. Simpson’s Heisman was hidden away at the LAPD’s request, then put back on display. Then it was stolen.

A USC custodian who came in for work at Heritage Hall on the morning of July 28, 1994, first noticed the empty case. Heisman No. 2, the jersey and a plaque describing Simpson’s gridiron greatness were all gone. Investigating officers didn’t find any evidence of a high-tech heist. Instead, they found that four screws had been removed so the clear box could be simply lifted off of the black pedestal and its contents taken. They immediately suspected it was a two-person job. But they also found there were no video surveillance cameras in the building, despite a spring 1994 report in the Daily Trojan that women’s basketball coach Cheryl Miller caught someone trying to take Charles White’s jersey from his Heisman display. There were no witnesses and no helpful fingerprints.

Amid the swell of media attention surrounding Simpson’s arrest, the theft of Heisman No. 2 went largely unnoticed outside of L.A. That was good news for one Lewis Eugene Starks Jr.

In 1994, Starks was 35 years old, described by the LAPD as a career criminal after being convicted of burglary in 1987 with a rap sheet that already included a dozen court appearances on various drug and theft charges.

Today, he is nearly 60 years old and has remained adamant that he was not one of the thieves who burgled Heritage Hall. However, Starks confessed that not long after Heisman No. 2 disappeared from USC, it was in his possession. He says a friend stole it and was keeping it in South Central L.A., only minutes from the USC campus. That friend kept the trophy buried in his backyard so no one could find it, but according to Starks, his pal was much more cavalier with the jersey, routinely wearing it around the house as he took people, including Starks, out back to see the buried treasure.

Starks says he bought Heisman No. 2 from the friend for $600 and a used car. Then, while the Simpson murder trial was shifting into high gear downtown, he tried to sell the convicted football star’s most famous award. There were no buyers. So, he took a different tack, calling USC to see if there was a reward being offered for the trophy’s return. The person who answered the phone at Heritage Hall said there wasn’t. So, Starks was stuck with it.

For the next two decades, Starks was in and out of jail and Heisman No. 2 was in and out of apartments, garages and storage facilities. He removed the nameplate and kept it separated from the trophy so that if a parole search was called and the Heisman was found, it couldn’t be traced back to the USC theft. Heisman No. 2 was with Starks when he was free and with his friends and family when he was behind bars. When harder times forced Starks into the streets, he lugged the 45-pound trophy around with him, sleeping under the streetlamps of Los Angeles with his arms wrapped around an O.J. Simpson 1968 Heisman Trophy.

As Simpson himself was behind bars downtown, Heisman No. 1 was nowhere near the streets. It was still on display at Rockingham, the home now occupied by his own friends and family as they waited out the 11-month murder trial. On Feb. 12, 1995, the jurors of that trial made a field trip to Rockingham. The day before, Simpson’s “Dream Team” of lawyers gave the house an extreme image makeover, swapping out photos and artwork to make their client seem more likable to those jurors than his chosen decor might suggest.

Film depictions and stories written about that visit have portrayed those jurors as being wowed by Heisman No. 1, with some even posing to take photos with it. But that wasn’t the case. Judge Lance Ito didn’t think to keep Simpson’s attorneys from redecorating Rockingham, but he did think of the Heisman. It was moved into the garage and covered with a sheet during the field trip.

For the next three years, as Simpson was found not guilty in the criminal trial in late ’95 and as the wrongful death civil trial cranked up the next year, news of the Simpson Heismans went silent. Simpson was back at Rockingham, and Heisman No. 1 was back in its trophy case. Heisman No. 2 was stuffed into a closet somewhere in Los Angeles as the LAPD investigation of the USC heist had grown ice cold. There was one promising call from an attorney saying his client had it, but it turned out to be a fake. For a while, there was hope it might turn up randomly, the way Simpson’s Pro Football Hall of Fame bronze bust was found by road crews alongside I-77 in Cleveland in 1996, one year after it had disappeared from the museum in Canton, Ohio.

But no such breaks came. USC asked the Downtown Athletic Club to send the school a replacement, which it did. That one was on display in Heritage Hall, and the visitors were back, most believing they were seeing the ’68 original.

On March 9, 1997, Heisman No. 1 was suddenly back in the spotlight as the headliner of the inventory being taken of O.J. Simpson’s wealth. He was found liable for the deaths of Nicole Brown Simpson and Goldman in the civil suit, and the jury awarded their families, including Simpson’s two children with Nicole, a total of $33.5 million in compensatory and punitive damages. To make that payment, Simpson was forced to auction off his personal belongings.

The crown jewel of those belongings was Heisman No. 1. Fred Goldman, Ron’s father, had already said publicly that he looked forward to smashing it with a hammer. There were also reports the family would have it melted down and use the bronze to make pins they could wear to honor the murder victims. During Simpson’s depositions for the civil suit, he floated a story that Heisman No. 1 had been stolen from Rockingham, that someone had broken into the trophy case and taken it while he was out playing golf.

But as the civil trial progressed and Simpson’s inner circle realized they were going to lose, they started pulling his possessions from his homes in California and a condo in New York to either be sold off or hidden. His belongings were scattered into storage units and tucked away into the corners of their own homes. The operation moved into overdrive after the court loss became official, the most frantic time coming during one scrambling overnight effort after the Simpson family received a tip that a moving van hired by the Goldmans was arriving the next morning.

The effort to save Simpson’s belongings was led by Mike Gilbert, Simpson’s marketing agent, who revered the Heisman most of all, explaining, “It represented paradise lost, what O.J. was and what we all were before 1994, when we were still innocent.” His very first meeting with Simpson had taken place at Rockingham in 1989, and they agreed to work together quite literally beneath the glow of Heisman No. 1. The problem now was that it was indeed missing from the trophy case at Rockingham, and Gilbert had no idea where it had gone. Gilbert replaced the jersey and footballs in that case with replicas, the replacement jersey dragged through the backyard dirt to make it look as game-worn as the original. He hid those originals with his already sizable secret stash of other Simpson artifacts. The very stash that, 13 years later, Simpson believed he was rescuing from memorabilia dealers during an armed robbery gone bad that landed him in prison for nine years.

After orchestrating the trophy case swap-out, Gilbert went to Simpson to find out whether he knew the location of his Heisman. He did. He said he had given it to an attorney friend, who was holding Heisman No. 1 and other valuables in a Southern California condominium.

Meanwhile, the sheriff overseeing the collection at Rockingham called Nicole Brown Simpson’s attorney, John Q. Kelly, to say they couldn’t find the trophy. Kelly in turn called one of Simpson’s lawyers, Robert Baker, and offered a compromise. What if he could assure them Heisman No. 1 would end up in the hands of his clients, Simpson and Brown’s children, instead of landing with the Goldmans and their promised public destruction? Baker called Simpson with the pitch. As Kelly recalled for USA Today in 2016: “He said, ‘John, I talked to O.J. about your suggestion and Simpson has a message for you.’ I said, ‘Oh, what’s that?’ He said, ‘O.J. said to tell Kelly he’s got a better chance of winning the Heisman than me giving it to him.'”

As the months went by and the Heisman holdout continued, Simpson was faced with a Dec. 15, 1997, deadline to turn it over or risk going back to jail. The attorney friend couldn’t admit to his role in the shell game for risk of being disbarred, so it was agreed that Gilbert would take the blame and make up a story that he had it all along. He retrieved Heisman No. 1 from the lawyer friend’s condo and delivered it to one of Simpson’s actual attorneys, Ron Slate. But moments before walking the trophy into the office, Gilbert removed the brass nameplate, pulling out the four small nails and stuffing the five pieces into his pocket.

Later that month, Gilbert was in New York for the Heisman presentation. He says he asked a friend in the Heisman offices to borrow one of their in-house trophies, knowing they kept spares, generic promotional models and some that were slightly damaged. He pulled the 1968 O.J. Simpson “Downtown Atletic Club” nameplate from his pocket, affixed it to a generic Heisman, placed that day’s New York Times next to it, ransom photo style, and took pictures.

After sticking the plaque back into his pocket and returning the trophy, he circulated the images to a tabloid and throughout the sports memorabilia community to create doubt about the authenticity of confiscated Heisman No. 1. If it found its way onto the auction block, he hoped to drive down the price and keep money out of the pockets of the Browns and Goldmans.

Over the first several months of 1998, Gilbert was hounded by the courts to turn over the nameplate. In his 2008 book “How I Helped O.J. Get Away with Murder,” Gilbert estimates he spent upward of $20,000 in legal fees fighting to keep it. Ultimately, he was told that if he continued to hold on to the trophy, he would be jailed.

According to Gilbert, Simpson told his friend and agent of nearly a decade that it was time to give it up and turn it over. No one needed to go to jail again. Then Simpson asked to hold the nameplate.

When Gilbert handed it over, he says the 1968 Heisman winner walked it into the kitchen, opened a drawer, grabbed a knife, and started furiously trying to scratch and deface the plaque before it became someone else’s.

One year later, on Feb. 17, 1999, Heisman No. 1, complete with a scratched 1968 nameplate, sat on display at the auction house of Butterfield & Butterfield in the Hollywood Hills. Other Simpson sports memorabilia was sold as well, including the jersey from Rockingham, bought by a Denver conservative Christian radio host and burned on the steps of the courthouse where the criminal trial was held. The polyester exploded, the first real sign that it wasn’t the authentic 1968 wool USC uniform.

When Heisman No. 1 was finally open for bidding, the room buzzed. At the time, there were 64 player-owned Heisman Trophies in the world, and this was the first to be sold. The cost did not skyrocket to the levels some predicted, but the final price tag did reach $255,000, purchased by an anonymous bidder from the East Coast. Two days later, that bidder showed up, and, standing in the middle of Hollywood, he was right out of central casting.

Tom Kriessman is as Philly as can be, with a likable, snarky sense of humor, a frequently broken volume knob and a soft spot for the Philadelphia Eagles. On Feb. 18, 1999, the sheet-metal wholesaler mugged for cameras with his new purchase, striking the stiff-arm pose, comparing his new trophy to the Liberty Bell and cracking, “I feel like I just won the Heisman!” Kriessman even produced his own nameplate to jokingly replace the one damaged by Simpson, pulled off of an MVP trophy he’d earned playing with a Philly amateur football team. It revealed that his nickname then was the same as the original owner of Heisman No. 1, reading “Tom ‘Juice’ Kriessman, 1979 Lackman League.”

When asked why he bought it, he explained to a laughing media contingent, “You always have to keep impressing your girl!”

Tom Kriessman was 47 then. More than 20 years later he’s still in Philly. He’s still in the sheet-metal business. And yes, he still has Heisman No. 1. But he hasn’t looked at it in a while. No one has. That day in ’99, when he met with the media, he explained his plans for it, to be displayed on his mantel and at work for a little while and then stuck in a bank safe to hold on to as an investment. That’s what he did. And as the years went by, people forgot about his big purchase. His newer friends had no idea he owned O.J. Simpson’s Heisman until 2013, when The Washington Post wrote a story tracking down every Heisman awarded to that point. He agreed to an interview, said his prize was still in an undisclosed Philadelphia area safety deposit box and admitted, “You just get caught up in things sometimes.”

Since then, more interview requests continue to roll in each fall as the year’s Heisman ceremony approaches, or whenever a Simpson trial anniversary rolls around. Kriessman is polite about it all. But, to put it in Philly terms, it’s become a pain in his ass. He will not reveal his ultimate plans for Heisman No. 1. But he does confirm he is still in possession of it. In 1999, he closed out his post-auction news conference by fielding a question on whether he felt as if he was depriving Simpson or his children of having his most beloved treasure. “I didn’t take it away from O.J,” he said. “Besides, if he wanted it, buy it. I don’t think he has the money.”

No one had the money or desire to take Heisman No. 2 off Starks’ hands. In the fall of 2014, Starks had once again emerged from prison, and he was broke. He was still unable to find a buyer. Either they didn’t trust a man with his rap sheet or they assumed that what he had was another fake. At one point he’d even tried to have a drug-related jail sentence reduced in exchange for returning Heisman No. 2. The court also didn’t believe him.

So, Starks turned back to his original plan from ’95. He would call USC to see if there was a reward.

When a young Heritage Hall front desk worker answered, Starks claimed he had their missing O.J. Simpson Heisman Trophy. The student, perhaps not yet born when the original Heisman No. 2 was stolen, looked over at the trophies displayed in the lobby. The second Heisman in that line of columns clearly had Simpson’s name on it. The USC employee told Starks he couldn’t possibly have their Heisman because it wasn’t missing, then hung up.

Confused but undeterred, Starks reached out to the Heisman Trust in New York, the organization formed in 2002 to take over presentation and management of the Heisman Trophy from the Downtown Athletic Club. Starks told them he had a Heisman and needed to have it authenticated. They asked him to take some photos and email them. He did. In an instant they knew it was USC’s missing Heisman No. 2.

The Trust gave a heads-up to USC, which called the LAPD, which handed the case over to Detective Don Hrycyk, the leader and only member of the LAPD Art Theft Detail. In nearly 25 years as LA’s only “art cop,” Hrycyk’s work led to the recovery of hundreds of millions of dollars’ worth of stolen art, from Picassos and Rothkos to Walt Disney animation cels and a $3.5 million Stradivarius cello. He started that job in 1994, shortly after the Heritage Hall heist. So, although he had never worked the case, he was familiar with the story and extremely familiar with the area. His original beat was in L.A.’s Southwest Division, which includes the USC campus.

“From moment one, USC was incredibly helpful. They really wanted to see if there was a chance to recover this item that had been gone 20 years,” Hrycyk said. But he remains puzzled at the decidedly different reception from the Heisman Trust, which was reluctant to give up any information to help the LAPD track down the man who had emailed them the photos for authentication. “It really was a hot potato they didn’t want to touch.”

When told of Hrycyk’s account, Heisman Trust executive director Rob Whalen did not comment specifically on the level of cooperation, except to say of the details surrounding the initial exchange with Starks: “Yes, that’s exactly what I recall.” (Whalen also said he had never heard the story of Mike Gilbert’s 1999 borrowing of the “generic” Heisman for his fake-out photos, which took place three years before the Heisman Trust was formed.)

It wasn’t long before the school received a second phone call from Starks, now emboldened by his Heisman No. 2 authentication. This time nobody hung up. With Hrycyk listening in and providing guidance, longtime USC sports information director Tim Tessalone talked with Starks and set up a day and time for a meeting to let the school see the trophy, determine whether it was the real deal and whether there might be some sort of reward.

The sting was on.

On Tuesday, Dec. 16, 2014, Tessalone stood out in the open of Heritage Hall while Hrycyk and his colleagues, warrant in hand, waited nearby. A taxi pulled up, and the man who got out was far from the vision of a frightening criminal mastermind. It was the graying 55-year-old Starks, and he looked tired. He was carrying a duffel bag, and when he unzipped it, there were three pieces inside. A scuffed-up dark wooden geometric base, a brass nameplate in need of some polish and a chunky bronze football player with a football tucked into his left arm and his right arm ready to deny a tackler. It was caked with some mud, dust and god knows what else, but it was definitely Heisman No. 2, back in Heritage Hall for the first time in 7,446 days.

Hrycyk moved in. Starks did not put up a fight. Far from it. They went into a Heritage Hall conference room, where the detective started asking questions and Starks answered them all. He was adamant that he hadn’t stolen the trophy and told the story of his friend who supposedly had, though he refused to reveal that friend’s name. He told of his $600 purchase but was inconsistent at best about the inclusion of the car in the trade. He didn’t have the jersey. Perhaps his friend was still wearing it around the house. But in the end, Lewis Starks Jr. readily admitted he’d had Heisman No. 2 since nearly the beginning. Those in Heritage Hall didn’t see remorse in the criminal’s eyes. They saw relief. He said he would have given it up even if there hadn’t been a reward. After 20 years, he just wanted to get rid of the damn thing.

The questioning took a while. When it was over, the LAPD assured Starks it would be in touch soon and left with the dismantled Heisman No. 2. Starks, with no reward money in his pocket, asked the people in Heritage Hall if he could have a few bucks to get home. They gave it to him.

The statutes of limitations on cases of theft run in the three-to five-year range, so after two decades, the most Hrycyk and Deputy District Attorney Casey Higgins could pursue was a felony charge of receiving stolen property. During spring 2015, they worked on an aggressive case against Starks, preparing to argue that he denied an entire generation of USC football fans the ability to see the real Heisman No. 2, to subpoena the Heisman Trust for phone and email records, and to identify Starks as an accomplice in the heist. To this day, the identity of the July 28, 1994, thief — or thieves — remains a mystery. But it wasn’t hard to shape a solid case against Starks. During his questioning at Heritage Hall, Starks explained to Hrycyk that he couldn’t have been involved in the theft because he was in prison at the time. But when the detective called the Department of Corrections, they said Starks was released before July 28. In fact, that very week in ’94, Starks reported to his parole officer in Exhibition Park, located across the street from the USC campus and about a 10-minute walk from Heritage Hall.

In September 2015, Starks pleaded not guilty. But the case languished, stuck on a shelf until summer 2016. By that time, there were leadership changes in the district attorney’s office and the supervisors overseeing the USC Heisman case handed down orders to make the mess go away so they could focus on more pressing matters than a missing football trophy.

On June 30, 2016, Starks was offered what Hrycyk calls a “sweetheart deal.” Starks changed his plea to no contest in exchange for a sentence of three years’ probation, and he received credit for less than a week already served in custody. One week later, Heisman No. 2 was returned to USC for good.

Today, the O.J. Simpson Heisman Trophy is easily distinguishable from its five bronze Heritage Hall counterparts. It’s the only one that has been touched by so many hands that the top of the player’s head has been polished down to a bright orange shine, though there is still some debate among those at USC as to whether the award on display is actually the returned original Heisman No. 2 or is still the replacement that held down that spot in its stead. Whichever one it is, it’s now securely anchored atop a podium specifically designed to thwart any would-be copycats, a critical part of 2014’s $35 million Heritage Hall renovation.

The true identity of the thieves will also likely never be known. Starks sticks by his account of how he acquired the trophy. In April 2019, Hrycyk retired after more than four decades on the force when he was informed that the Art Theft Detail was among a list of smaller departments that were being shuttered by the LAPD. When pressed on Starks as a suspect, Hrycyk said, “It’s hard to say because it is still up in the air. … But from here, Lewis looks pretty damn good.”

It is still up in the air. The investigation is still considered open because the jersey that accompanied Heisman No. 2 remains missing, so current LAPD officers won’t comment about the case publicly. But they also know they are unlikely to ever find that final missing piece.

Once lost forever, Heisman No. 2 now belongs to the people of Troy, while Heisman No. 1 might not be seen by the public ever again, at least not without a sizable price tag. This October, Ricky Williams’ 1998 Heisman Trophy sold at auction for $504,000, significant because ’98 was the last year that a Heisman winner was not required by the Heisman Trust to sign an agreement forfeiting his right to sell it. One year earlier, 1987 winner Tim Brown’s award went for $435,763.

In theory, O.J. Simpson could one day own Heisman No. 1 once again, but that’s assuming Tom Kriessman ever attempts to sell it. He refuses to comment on his plans. But even if Kriessman sticks to his original investment strategy, Simpson would certainly have difficulty overcoming the same issue Kriessman pointed out at his auction house news conference in 1999. Even if the man whose name is on the trophy were allowed to make a bid, could he come up with enough cash to make a run at a purchase?

Simpson could not be reached for comment for this story. But he has said in the past that he doesn’t understand why someone would want to own a trophy earned by someone else.

“These types of things, like a Heisman Trophy, they usually just disappear, and if they turn up, they’ve either been found in storage somewhere or they’ve just been given up. There’s a reason for that,” Hrycyk explains. “Once the thief has it, they don’t realize how difficult it is to get rid of something that means too much, that is too high-profile. It’s been on TV. It’s been in the newspapers. The very things that make it so valuable to the world make it of no value to them at all.

“I’m not saying that holding on to something like an O.J. Simpson Heisman Trophy is a curse. But it certainly doesn’t seem to look like it’s much fun, does it?”